A Chicago teenager pleaded with Cook County Judge James Linn to impose the maximum prison sentence on the man who sexually assaulted her and her two sisters for several years and threatened to kill them if they told anyone.

“Help us ensure that there will be one less rapist out on the streets,” the woman, then 19, wrote in a victim impact statement read aloud at the sentencing hearing in May 2011. “At the end of the day, I just want justice to be served the correct way. With absolutely no leniency, because he didn’t show us any.”

But in a huge break for the defendant, Joseph Fultz, Linn took the extraordinarily unusual step of reversing the jury’s verdict and convicting him of a far less serious sex charge. Linn then sentenced Fultz to 18 years in prison, a far cry from the mandatory life sentence he faced if the jury’s decision had stood.

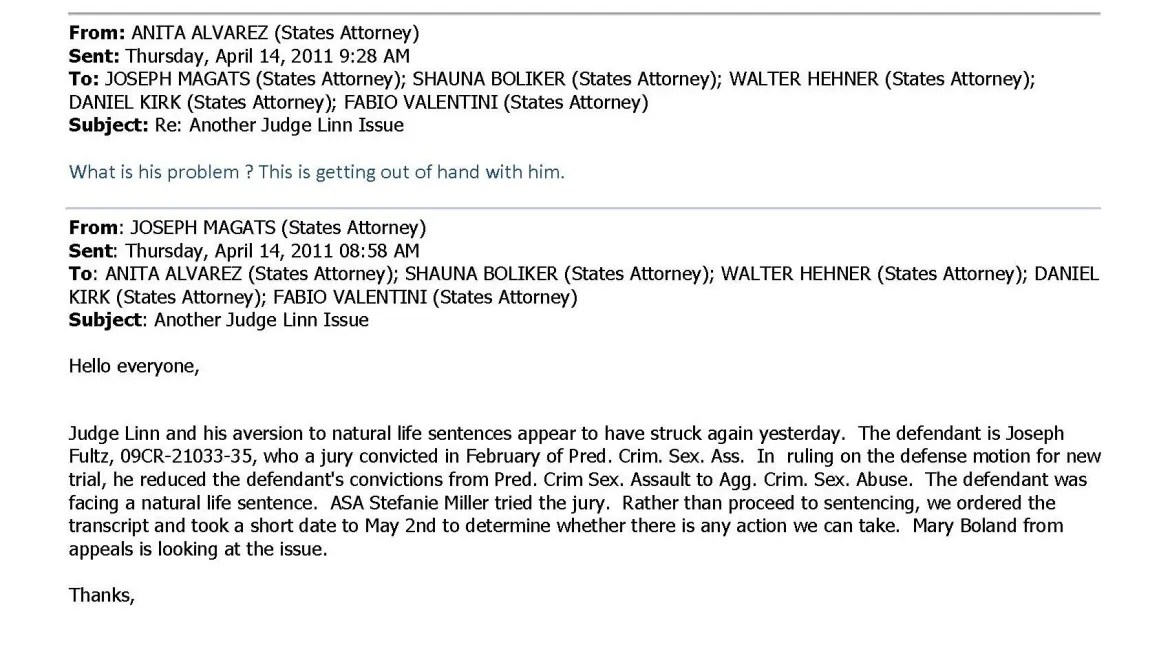

For the Cook County state’s attorney’s office, the about-face marked the final straw following a series of what prosecutors viewed as unfavorable decisions by Linn on sex cases, according to internal office emails and interviews with several former prosecutors.

“What is his problem?” then-State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez wrote of Linn in an email at the time. “This is getting out of hand with him.”

The state’s attorney’s office soon began regularly using an obscure legal maneuver to remove Linn from any sex cases assigned to him, filing what’s known as motions for a substitution of judge, or SOJ. No reason had to be given to boot Linn, and a new judge would be quickly appointed in his place.

In less than two years following his controversial handling of Fultz’s case, Linn was bounced from at least 25 sex cases using SOJs, about four times more than the next closest judge, according to an unprecedented analysis of criminal court data.

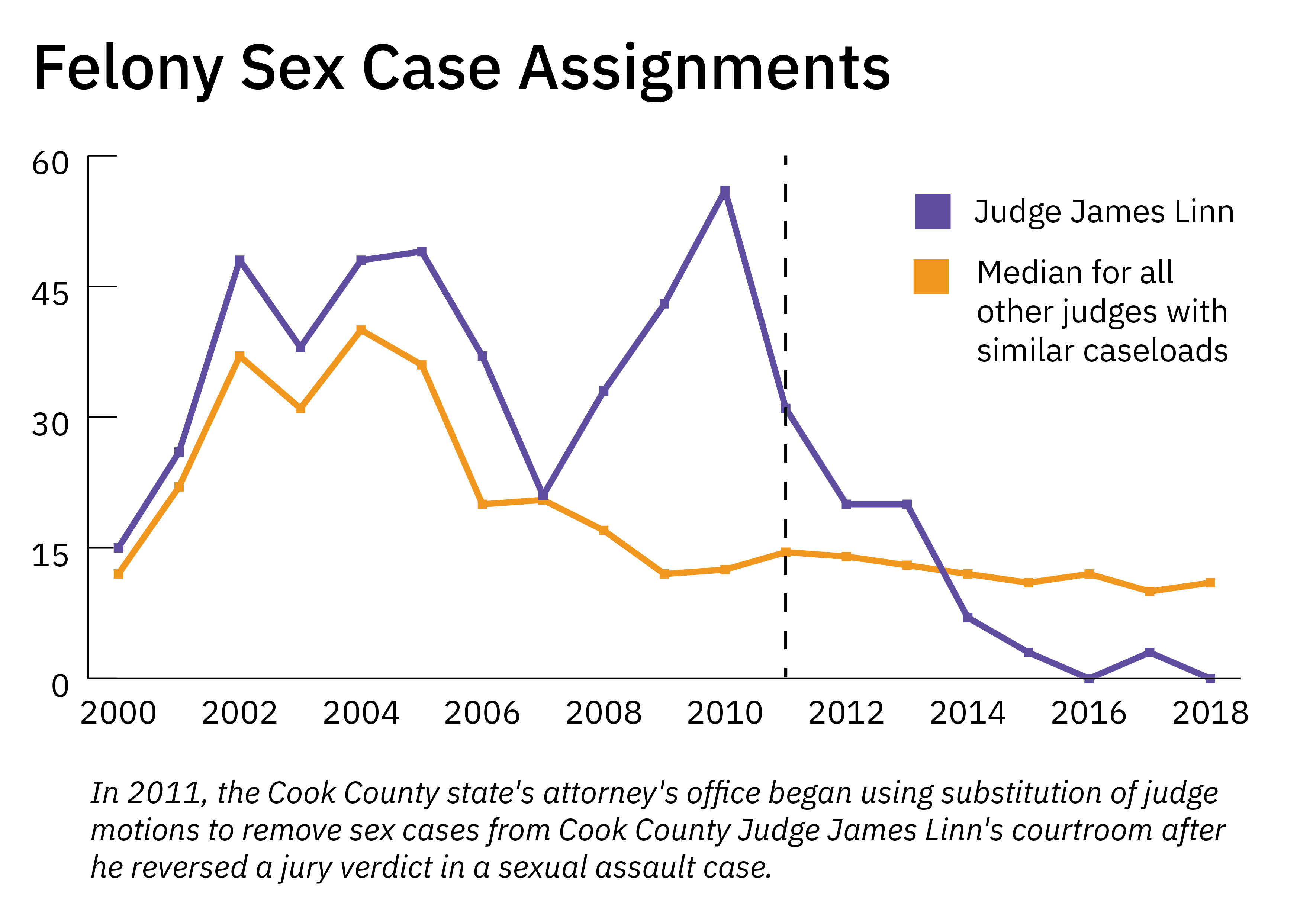

Then something yet to be fully explained happened: The number of felony sex cases randomly assigned to Linn by computer sharply decreased in following years, suggesting that court officials, aware of the state’s attorney’s campaign, largely stopped assigning sex cases to Linn.

As a result, Linn hasn’t presided over a sex case since November 2013, after having overseen more bench trials involving sex crimes than any other Cook County judge the previous 13 years. This finding emerges from the analysis by The Circuit, a new investigative collaboration by the nonprofit news organizations the Better Government Association, Injustice Watch and The Chicago Reporter.

Speaking out for the first time, three women who testified in Linn’s court say the judge’s lenient treatment of sex offenders left them feeling victimized twice over — first by the sexual assaults and then by a judge who didn’t fully believe them.

Linn “didn’t really think about the emotional damages that (Fultz) left on me or my sisters or the full nature of how sick he was,” said the youngest of the victims, who was just 12 years old at the time of his sentencing.

The woman, now 22 and a mother of two, issued a statement saying she didn’t think she’d ever regain her faith in the justice system.

“And it’s not because of the case,” wrote the woman, who is Black. “It’s because most of the time people don’t care about people that look like me or that have my kind of background. That’s why so many people take (the) law into their own hands.”

Linn, currently presiding over high-profile charges that actor Jussie Smollett staged a hate crime, declined to comment to The Circuit through a court spokeswoman.

Fewer sex crime cases heading Linn’s way

The Circuit’s monthslong project, which includes a first-ever analysis of more than two decades of court data on nearly one million Cook County felony cases, examined SOJs because many attorneys consider a large number of such motions to be a potential red flag for a judge’s fairness or temperament.

Between 2000 and 2013, Linn presided over more bench trials involving sex crimes than any other Cook County judge, a measure of defense lawyers’ comfort level in letting the veteran judge — and not juries — decide their clients’ fates, The Circuit analysis found.

More than other judges, Linn showed a tendency to find defendants facing sex charges guilty but on less serious offenses. Between 2000 and 2013, he did that at least 13 separate times in 67 bench trials involving sex charges he handled, according to the analysis. No other Cook County judge came close.

In reviewing the large number of SOJs filed against Linn by prosecutors for both State’s Attorney Kim Foxx and her predecessor, Alvarez, The Circuit also found a pattern in which the criminal division’s presiding judge — who is supposed to randomly assign all cases to lower-level judges — largely stopped referring sex cases to Linn.

That pattern was reflected in an internal email from a top prosecutor in Foxx’s office that was obtained under a Freedom of Information Act request by The Circuit.

“We’ve been SOJing (Linn) on sex cases so long that the last two presiding judges do not even send them to him,” wrote Joseph Magats, then-chief of the state’s attorney’s criminal prosecutions bureau and now Foxx’s first assistant, to a higher-up supervisor in 2017.

But the analysis of the court data paints a more complicated picture than Magats’ assertion. Since 2014, only a handful of sex cases were assigned each year to Linn but then quickly transferred by an SOJ to another judge. In both 2016 and 2018, however, the analysis of The Circuit’s data didn’t find that any sex cases had been randomly assigned to Linn.

That represents a stark contrast from the period 2000 through 2013, when Linn was randomly assigned by computer an average of almost 35 sex cases per year, the analysis found.

With fewer sex cases being assigned to Linn, prosecutors haven’t had to SOJ him as a much in recent years — a plus for the state’s attorney’s office, since the motions risk offending judges who preside over hundreds of criminal cases.

Despite the dramatically fewer sex charges going to Linn, Judge LeRoy Martin Jr., who presides over the criminal division, insisted that all cases are still assigned randomly to the division’s judges, according to a statement released on his behalf by the Cook County chief judge’s office. He declined through a court spokeswoman to be interviewed for this story.

Martin’s predecessor, Paul Biebel Jr., who retired in 2015, also denied making any changes during his tenure to the computerized random assignment of criminal cases.

Magats did not return calls or emails, and Alvarez declined to comment. Foxx did not respond to a request to be interviewed, but her office issued a brief statement through a spokeswoman that said decisions to SOJ Linn on sex cases were “based on information available at the time.”

While prosecutors have repeatedly sought to block Linn from hearing sex cases, their disdain for him does not carry over to other serious felonies, the analysis found.

What’s more, several defense attorneys spoke in support of the judge’s handling of sex charges, saying Linn simply held prosecutors to proving their case — sex charges or not — beyond a reasonable doubt.

Indeed, in more than three decades on the bench, Linn has imposed lengthy sentences on sex offenders. In 2002, for instance, he sentenced Mark Anthony Lewis to 120 years in prison for raping a 15-year-old North Side girl.

“He starts out unbiased,” said attorney Keith Thiel, who had two clients acquitted by Linn on pimping and prostitution charges in 2013, one of the last sex crime bench trials overseen by Linn. Adding that he’s tried more than a dozen cases before Linn over the years, Thiel said, “I don’t find him to be state-oriented, but I don’t find him to be defense-oriented, either. He’s really middle-of-the-road. … He puts everyone’s feet to the fire.”

Raul Villalobos, a longtime defense attorney and former Cook County prosecutor, said Linn, whose father also served on the Cook County bench, is unafraid of controversy.

Villalobos recalled a client who faced predatory criminal sex assault charges for allegedly raping a 7-year-old boy. Linn convicted him of lesser sexual abuse charges in June 2012 and sentenced him to three years in prison.

“(If) he thinks someone is guilty, he will find them guilty,” Villabolos said. “But he holds the state to a burden of beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Questions of ‘forum shopping’

Around the same time the state’s attorney’s office was substituting Linn on sex cases, it was using the same playbook on another judge for a different reason, The Circuit investigation found.

Since 2013, prosecutors moved to SOJ Judge Ann Finley Collins, assigned to the west suburban Maywood branch, more than a dozen times on drunken-driving cases. The SOJs came after a court-watchers group and police in suburban Riverside appealed to the county’s chief judge following several acquittals and pretrial rulings favorable to defendants by Collins in drunken-driving cases.

Collins, a former assistant public defender, didn’t respond to repeated calls and emails seeking comment.

While moving to substitute Linn and Collins indicates that prosecutors view those judges as biased, some legal experts called into question the state’s attorney’s practice of routinely substituting a judge on certain types of cases.

Frank Cece Jr., a longtime defense lawyer and former assistant state’s attorney, said the moves were obvious attempts by prosecutors to gain a more favorable outcome.

“For (the) state to be forum shopping as a pattern and practice with one judge is beyond the pale,” he said.

Bennett Gershman, a law professor at Pace University in White Plains, New York, and an expert on prosecutorial ethics, also expressed concern that the routine substitutions of a judge could represent an overreach by prosecutors.

“It strikes me as misusing the ability to remove (judges) … in a way (to) skew the proceeding to better benefit the prosecutor,” he said.

The ability to substitute judges in Illinois was first accorded to just defense lawyers, but the Illinois Supreme Court extended the right to prosecutors in a decision more than three decades ago.

Patricia Brown Holmes, a former Cook County judge and federal prosecutor who successfully argued that case, said SOJs give lawyers “the ability to feel like any particular judge is not just handed to you and you can’t do anything about it.”

On occasion, though, the regular use of SOJs by prosecutors against the same judge has become a point of contention.

In 1990, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled that the state’s attorney in St. Clair County in Southern Illinois could not use the motions to repeatedly block a judge from hearing felony cases in an effort to force his reassignment to another court call.

More than a decade later, Cook County Judge Leo Holt complained that the state’s attorney’s office had been engaging in a pattern of removing serious felony cases from his call through the use of repeated SOJs after his assignment to the county’s main criminal courthouse at 26th Street and California Avenue. Prosecutors denied the allegations and took the fight — with mixed results — to the Illinois Supreme Court on a number of occasions after Holt refused to step aside from a handful of cases.

The now-deceased Holt was Black and helped defend Martin Luther King Jr. as a private attorney during the open housing marches in Chicago in the 1960s. Holt had a reputation for handing out lighter sentences and acquittals, contended detractors who derisively nicknamed him “Let ’Em Go Leo.” His supporters argued that the prosecutors’ campaign against him was racist.

Around the same time, another Black judge, James L. Rhodes, who handled juvenile cases and felonies in the south suburban Markham branch courthouse, successfully challenged prosecutors on their efforts to regularly substitute him, as well.

“Their idea with what to do with juveniles is just to lock everybody up,” said Rhodes, now retired, in a recent interview. “Since I didn’t agree with that, I didn’t do that. …They didn’t want to send cases to me.”

‘A slap on the wrist’

Before Linn’s reversal of Fultz’s jury verdict, his handling of other sex cases had drawn the ire of the state’s attorney’s office.

At about the same time as Fultz’s sentencing in 2011, Linn found Robert Rowels, a parole officer for the Illinois Department of Corrections, guilty of custodial sexual misconduct and official misconduct for threatening a female parolee in her 20s with prison if she didn’t repeatedly have sex with him.

But the judge acquitted Rowels of more serious sexual assault charges despite what authorities said was DNA evidence implicating him. Rowels, who faced at least four years in prison if he had been convicted of the more serious charges, was sentenced by Linn to 120 days in the Cook County Jail and two years of probation. Rowels declined to comment for this story.

In a telephone interview, the victim in that case said she had never been told much by the state’s attorney’s office about what happened to Rowels beyond his conviction. When a reporter from The Circuit shared more details about the outcome from nine years ago, the woman called the short jail sentence “heartbreaking.”

“Basically, he got a slap on the wrist,” said Kimeda McGinnis, who chose to go public with her name for this story in hopes of helping in her own healing and perhaps inspire other rape victims to come forward.

McGinnis, who moved out of state after the ordeal, doesn’t regret coming forward with the DNA evidence despite the case’s ultimate outcome and the retaliation that she said she experienced from her next probation officer.

“It can break your soul if you let it,” she said.

Earlier that year, in another surprising about-face, Linn threw out the sexual assault conviction that he had issued against Ryan Logan, who lived in Chicago’s River North neighborhood.

The decision came in February 2011, just months after Linn found Logan guilty of raping a 31-year-old woman he met on Match.com while acquitting him of the sexual assault of another woman he met on the dating website. Instead, Linn reduced Logan’s conviction to a lesser count of sexual abuse and sentenced him to just 90 days in jail. Logan had faced up to 15 years in prison before Linn downgraded the rape conviction.

Attorney Daniel Kirschner, who represented the victim in a lawsuit against Logan and Match.com, said Linn reduced the conviction after Logan completed treatment at a facility for sex offenders.

“My client was not terribly pleased,” Kirschner said recently.

Another decision that drew scrutiny came in 2009. Linn found George Turner III, the boys basketball coach at Walter Payton College Preparatory High School at the time of the abuse, guilty of molesting two female students but acquitted him of the more serious charges of sexually assaulting one of the teens. Linn sentenced Turner to three years of probation and fined him $25,000.

In an interview, one of the survivors, Camille Rodriguez —who also wanted to go public with her name for this story — said she learned not to trust the legal system after Linn cleared Turner of the more serious charges involving her in spite of her testimony at trial.

Rodriguez said she still recalled Linn saying he thought something had happened but not to the degree that she had described.

“To know that I sat in that courtroom with a bunch of adults bashing me, saying a 15-year-old could seduce (a) 30-, 40-year-old … led me to believe that I didn’t do a good job at really displaying what happened,” said Rodriguez, now a social worker who lives out of state. “It wasn’t him on trial; it was me on trial.”

A lawsuit filed by Rodriguez alleged that Turner raped her repeatedly when she was a manager of the boys basketball team.

Rodriguez, who still holds on to the trauma more than a decade after the trial, said a prison term wouldn’t have healed her pain but would have helped in other ways.

“It would have at least led me to believe that somebody gave a shit,” she said. “This internalized guilt is irrational. I know that with every fiber of my brain, but I haven’t come to terms with it.”

Turner did not return multiple calls seeking comment.

Reversing a jury’s finding

It was just weeks before Fultz’s sentencing in May 2011 that Linn made the stunning announcement. Months after the jury found Fultz guilty of predatory criminal sexual assault for the repeated attacks on the three underage girls, Linn downgraded the conviction to aggravated criminal sexual abuse, a far less serious offense.

At the hearing, William Woelkers, an assistant public defender representing Fultz, asked Linn to throw out the jury’s conviction, pointing to what he said was a lack of physical evidence and inconsistent testimony by the three girls at the trial, according to court records.

Stephanie Miller, the lead prosecutor, strenuously objected to Linn’s decision, noting that the jury, not the judge, was in a “far superior position” to determine the truthfulness of the victims’ testimony.

“We’d ask that you not disturb the jury’s verdict,” she said, according to a transcript of the hearing.

In his ruling, Linn noted that state law required a life sentence for a conviction on the predatory criminal sexual assault charges and questioned whether the crime met the definition of a charge that required penetration.

“I believe that the children were molested,” the judge said. “So I will adjust the jury’s findings over the government’s strong objection. I cannot say that strong enough. They are absolutely objecting to the court considering this.”

In a letter read at Fultz’s sentencing, the mother of the three victims lamented how she hadn’t initially believed the girls’ stories of assault.

“They’ve had to tell this story over and over again. That’s hard for a rape victim; it’s hard for me to hear and see the hurt on their faces,” the mother wrote. “The confusion of wondering why no one … helped them, including myself. It’s been hard to find a smile from them on some days.”

The middle sister said in her victim impact statement that Fultz haunted her dreams, and that she lived in fear that he would follow through on his threats to kill her and her sisters if he was ever released.

“I just hope that justice will be served,” she wrote.

Woelkers, Fultz’s attorney, asked for mercy, noting Fultz’s tragic life. He was sexually abused as a child, dropped out of Harper High School as a sophomore because of a learning disability, and attempted suicide in 1999 after his young son and girlfriend were murdered, according to court records.

Linn sentenced Fultz to 18 years in prison — a sharp contrast to the mandatory life sentence that he once faced. Fultz ended up serving about half that time before his release from prison. He died early this year from heart disease, records show.

The youngest of Fultz’s victims said his death — as well as her going public with her story — has brought some measure of relief.

“I am still that little girl that was victimized,” she wrote in an email. “Every time I think of what he was or be reminded of what he did, I still feel like a victim. But thinking about where I was then and now, I am a survivor.”

Emails obtained from the state’s attorney’s office in response to the FOIA request make it clear that Linn’s reversal of the jury verdict marked a breaking point for the office.

“Judge Linn and his aversion to natural life sentences appears to have struck again yesterday,” wrote Magats of the state’s attorney’s criminal prosecutions bureau, in notifying the higher-ups of the decision in April 2011.

Alvarez expressed concern, as did Daniel Kirk, her chief of staff at the time.

“We are going to have to do something,” Kirk wrote of Linn in the email chain. “He is getting worse.”

The next month, Linn was randomly assigned the case of Cortez Foster, a homeless man accused of sexually assaulting and robbing a grandfather in Grant Park.

Prosecutors quickly moved to transfer Linn from the case. Another judge later sentenced Foster to life in prison.

Data analysis for this story was conducted by Forest Gregg and Hannah Cushman Garland of DataMade and Jared Rutecki of the BGA.

This story is part of The Circuit, a joint project of the nonprofit news organizations Better Government Association, The Chicago Reporter and Injustice Watch, in partnership with the civic tech consulting firm DataMade. The Circuit was made possible with support from the McCormick Foundation.