Charles Randle, once an inmate at Stateville Correctional Center, recalled waking up one morning in that prison with a roach inside his ear.

Billy Johnson, who lost his hearing at 2-years-old due to an illness, said he can’t earn his GED at the Danville Correctional Center because prison officials won’t provide a sign language interpreter.

Aaron Fillmore, locked up for 25 years in solitary confinement at a handful of Illinois prisons, says he doubts he is mentally fit to share a cell.

All three men have been plaintiffs in federal lawsuits filed against the State of Illinois, alleging that their constitutional rights were violated by the Illinois Department of Corrections, which houses about 30,000 people in the state’s prisons. Over the years, judges have taken the unusual step of certifying these complaints as class actions and, in some cases, have ordered the state to improve conditions for inmates who are deaf, mentally or physically ill, held in solitary confinement or housed at Stateville Correctional Center, which inmates say is dilapidated and filled with vermin.

Progress has been slow as the bill to taxpayers keeps rising. Court-ordered audits show the IDOC continues to fail to provide basic care to inmates — a point underscored by the Illinois Answers Project in interviews with more than a dozen people who are incarcerated. The state has paid more than $13 million in legal fees and fines so far as part of the settlements and faces an ultimate tab of hundreds of millions of dollars to fulfill settlement requirements. Separately, a report published earlier this year estimates the state has a multibillion dollar backlog in maintenance expenses to repair its dilapidated prisons, some of which date to the 19th century.

David Muhammad, who was federal monitor of the Illinois parole system, said that there’s “no question” Illinois could have avoided the extra costs inherent in the settlement agreements if the IDOC operated a better system.

“The state could have just not treated inmates horribly,” said Muhammad, who is now the executive director of the National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform.

The IDOC denied the claims made by the plaintiffs in the lawsuits but declined to comment further in detail, citing the active litigation.

‘There’s no treatment occurring’

A federal lawsuit filed in 2007 alleged that mentally ill people in Illinois prisons were “subjected to brutality instead of compassion, and housed in conditions that beggar imagination,” spurring numerous reforms over the years.

Even as the quality of care remains in question 16 years later, a federal judge ruled in October to end the lawsuit for procedural reasons.

Attorneys who represent the inmates say they plan to appeal the ruling, which cuts off any future reimbursement of legal fees. U.S. District Court Judge Michael Mihm’s decision to end the case disappointed them, they said, because of the treatment gaps that still exist despite the sweeping changes to inmate mental health care that the lawsuit ushered into the state’s prison system.

Chief among those changes is the construction of a new mental health facility — the Joliet Treatment Center — and an in-patient treatment facility at the Joliet campus. State records show that in the past five years, the state has spent $213 million for these facilities and other lawsuit-related mental health improvements. Attorneys contend the in-patient facility, which has 200 beds, is barely used despite a significant demand.

A court monitor appointed to oversee the settlement said in an August 2022 report that more work remains. The IDOC was still noncompliant with broad swaths of the settlement agreement including evaluations and referrals, use of physical restraints, as well as use of force and discipline for “seriously mentally ill offenders.”

Muhammad, the former court monitor, said that settlement agreements such as the one for the IDOC’s mentally ill inmates can be effective “blunt instruments.”

“The challenge is sometimes they stick around way too long, sometimes some of the conditions are wonky and don’t make real practical sense,” he said. “But there’s a ton of reform that has occurred from them.”

The IDOC issued a statement that said the changes made as a result of the mental health care lawsuit “remain engrained in its policies and procedures.”

“The IDOC will continue to provide comprehensive mental health services for its residents in custody,” the statement said.

Patrice Daniels was the leading plaintiff in the lawsuit. He is serving a life sentence at the Joliet Treatment Center, a facility with single occupancy cells for inmates who have serious mental illness. He says he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and bears scars from self-inflicted cuts.

“There’s no treatment occurring,” said Daniels, who pleaded guilty to a 1994 murder in Grant Park in exchange for a sentence of life in prison instead of the death penalty, which was abolished in Illinois in 2011. “It’s only a treatment facility in name. Nobody is getting better in that sense.”

People in the prison, he said, are sent to the segregation unit if they act out as a result of their mental illness, which makes it worse.

“There are guys where, as a consequence of their severe mental illness, voices sometimes tell them to be violent towards other people,” Daniels said. “I present very well, but most people who aren’t clinicians don’t understand the challenge that it takes for me daily not to (self-harm).”

A 2016 survey of state and federal prisoners showed 41% of inmates reporting a history of mental illness.

Attorney Alan Mills of the Uptown People’s Law Center represents Daniels and other inmates in reform-minded lawsuits. He acknowledged the snail’s pace of progress but said that when the lawsuit began, mental health care in Illinois prisons consisted of monthly appointments where some people received medication and everyone else was placed into solitary confinement. Through several changes made in a 2016 legal agreement, people with diagnosed mental illness receive monthly check-ins with mental health staff or a mental health group, and everyone has a treatment plan.

“The quality of the treatment plan remains in question,” Mills said. “The problem is that getting a consent decree is, as hard as it may be, the easy part. Actually getting changes in the system is the harder part.”

Small steps in solitary confinement reform

A federal lawsuit filed in 2016 alleged that people in Illinois prisons were getting thrown into solitary confinement for long periods of time for “even the most minor prison infractions,” and “minimal processes” existed for people to prove their innocence.

The lawsuit said that people in solitary confinement live in “tiny, often windowless cages” that are smaller than the 50-square-feet prison cells that the Illinois Legislature requires for new construction of prison dorms, and likened the practice of using solitary confinement as punishment to torture.

Mills said that in response to the lawsuit IDOC officials rewrote their rules for solitary confinement to shorten sentences and provide a way for inmates to work themselves out of segregation.

Still, about 4% of the inmate population has remained in solitary confinement, a number that has remained mostly unchanged since 2017, court filings show. More than 5,400 inmates have spent at least one year in solitary confinement during the past dozen years. Eleven people have spent a dozen or more years in solitary confinement during that time.

Aaron Fillmore, 48, was first placed in solitary confinement after he was accused of having a role in a February 1997 scalding oil attack on a warden, his assistant and a guard, who visited him in his cell at Menard Correctional Center, court records show. He was later released from solitary but then returned to the segregation unit after he stabbed a Will County correctional officer, which he pleaded guilty to in 1999 in exchange for an additional 20-year sentence. He was transferred to Tamms Correctional Center, a maximum security prison in southern Illinois where most inmates spent 23 or 24 hours alone in their cells “without social interaction, human contact, or sensory stimulation,” according to one report. After Tamms’ closure 11 years ago, Fillmore spent time in solitary confinement at prisons in Pontiac and Lawrence before he was transferred in June to a New Mexico prison.

In correspondence with Illinois Answers written earlier this year, Fillmore described being locked inside his cell “basically 24/7.”

“Being in isolation, chained and shackled every place I go, forced to exercise in a small dog cage has taken a toll on my body and mind,“ wrote Fillmore, who was given a 75-year sentence connected to the 1994 murder of a Plano woman. “I have gum problems because I would brush my teeth so much out of just being bored.”

‘I been dealing with so much pain’

Research shows that prison conditions and the bare-bones health care offered behind bars can take years off a person’s life.

The dismal state of prison health care and outcomes for inmates is no different in Illinois, where the widely criticized private prison health care company Wexford has operated the state’s prison health care system since 2011 in exchange for more than $1 billion in taxpayer money.

A court monitor reported last year that the IDOC’s clinical care remains poor, record-keeping for vaccinations is non-existent, and there is no data to show that screenings for the two leading causes of cancer deaths within the prison system — liver and lung cancer — are being performed.

The monitoring was ordered through a settlement in the lawsuit that inmate Donald Lippert filed in 2010, alleging the IDOC denied him access to health care and refused to provide him with the food he needed to manage his diabetes.

In a phone interview, Lippert said he still gets meals of pasta and potatoes three times daily, which makes his blood sugar spike.

“It makes me feel tired, miserable,” said Lippert, who is serving a 140-year prison sentence in connection with multiple murders. “It takes a big toll on my organs, my blood vessels, my eyes.”

To date, the state has spent more than $5.5 million on costs related to the case.

According to interviews with attorneys and reform advocates, the overall bill for Illinois taxpayers — more than $13 million stemming from a handful of protracted lawsuits — is low compared with California, which generates millions of dollars in legal fees each year from similar cases. Inmates in Arizona, Georgia and Massachusetts have also used class action lawsuits to successfully challenge what they allege are civil rights violations.

Illinois’ latest prison health care monitor’s report said the patient care for inmates who are elderly, disabled or infirm is “consistent with neglect and abuse,” and that inmates with dementia signed “do not resuscitate” documents or wills when they “clearly were not of sound mind and could not willfully and voluntarily do so,” according to the report.

As of June, there were more than 1,200 inmates in the IDOC who are 65 or older.

One example in the report described a 74-year-old patient losing 61 pounds and then dying of septic shock, a perforated colon and rectal cancer in July 2021 after doctors failed to order a colonoscopy and diagnose the disease for a year and a half.

“This was a basic medical judgment issue that was addressed in an unsafe and harmful manner,” the report said, recommending the doctor for peer review.

Lazerrick Coffee, a plaintiff in the lawsuit, said IDOC refused to help him manage the pain he suffers from sickle cell anemia, which causes him to develop ulcers and experience extreme pain informally called a “sickle cell crisis.” He said prison officials removed him from the doctor-prescribed treatment — Tylenol and a painkiller — that he had taken for nine years ending in 2020, when he began his sentence.

“He told me that I was taken off the medication I was getting for 9 years because it’s a narcotic, but ever since I been off that medication I been dealing with so much pain,” wrote Coffee, who is serving a 13-year sentence at Pinckneyville Correctional Center for carjacking. “It gets to a point that I cry, my (cellmates) will try to help but they really can’t do nothing.”

The legal proceedings for the prison health care lawsuit have been fraught. Last year, a federal judge held the IDOC in contempt for failing to create an implementation plan as required by a consent decree.

A prison singled out for reforms

Ten years ago, Lester Dobbey filed a lawsuit alleging that Stateville Correctional Center in Crest Hill was filled with vermin, birds and mold, and other structural problems that made the facility hazardous to inmates’ health.

Dobbey told Illinois Answers in a phone interview about a wide range of safety and sanitary concerns at the prison: cracks separating the building from the roof, roaches freely scuttling around the food serving line, flocks of as many as 50 birds flying around the prison at night, expelling waste into the living quarters of inmates. He recalled one incident from when he was working in a kitchen, passing out what he thought were chocolate chip cookies from a garbage bag.

“I get to the bottom and it’s hundreds upon hundreds of mice pellets all in the bag,” said Dobbey, who has since been transferred to the Danville Correctional Center. “So I’ve been serving mice crap on cookies.”

An IDOC-commissioned master plan published in May estimated that the prison has $286 million worth of “deferred maintenance,” a significant part of the $2.5 billion maintenance backlog that exceeds the IDOC’s annual budget by $670 million.

The report took special aim at Stateville’s sleeping quarters, saying that its dorms “are not suitable for any 21st century correctional center.” Last year, hundreds of inmates were transferred out of the building after two water heaters at the facility broke down.

“The Quarterhouse particularly has a design developed during the penitentiary period of the 1800’s,” the study states, noting that $12 million in immediate structural repairs are needed.

The report suggested building new housing at Stateville to “help create a positive environment for staff and inmates.” The estimated cost for 700 new beds at Stateville? $72 million.

“The place is literally falling apart, the infrastructure is gone,” said Charles Randle, an inmate at Stateville from 2017 to 2021, when he was transferred to Menard. “You can’t do any major work or it will collapse. It’s like you’re trying to bring a dinosaur back to life.”

Heather Lewis Donnell, an attorney for the plaintiffs, said that since the lawsuit was filed, the number of people staying at the prison has plunged from more than 1,000 inmates to about 500 and the decrepit “F-House” dorm was closed, except for temporary use as a COVID-19 infirmary early on in the pandemic. She was unsure when the case would end but said that significant changes would need to occur before then.

“We’d like to see it be a humane, habitable prison for the residents,” Lewis Donnell said.

Hearing lawsuit ends

The IDOC was ordered to pay about $430,000 in fees and fines earlier this year as part of a settlement of a 13-year-old case that sought to provide interpreters and hearing aids for inmates who are deaf or hard of hearing.

Amanda Antholt, an attorney with the firm Equip for Equality that represented inmates in the lawsuit, said that IDOC reported in April 2022 there were 1,695 inmates in custody who identified as deaf or hard of hearing.

IDOC had agreed to screen new inmates for hearing, provide communication plans and hearing aids for inmates who were deaf or hard of hearing, and supply American Sign Language translators for all “high-stakes interactions” such as medical and mental health care appointments, disciplinary hearings, educational and vocational programs.

The IDOC noted in a January filing that in November 2022 there were 55 “high-stakes” interactions involving inmates who were deaf or hard of hearing and 48 of those involved an interpreter.

“Despite a few issues at the remaining facilities, the issues are sporadic, not systemic, and are resolved when they arise,” the report stated.

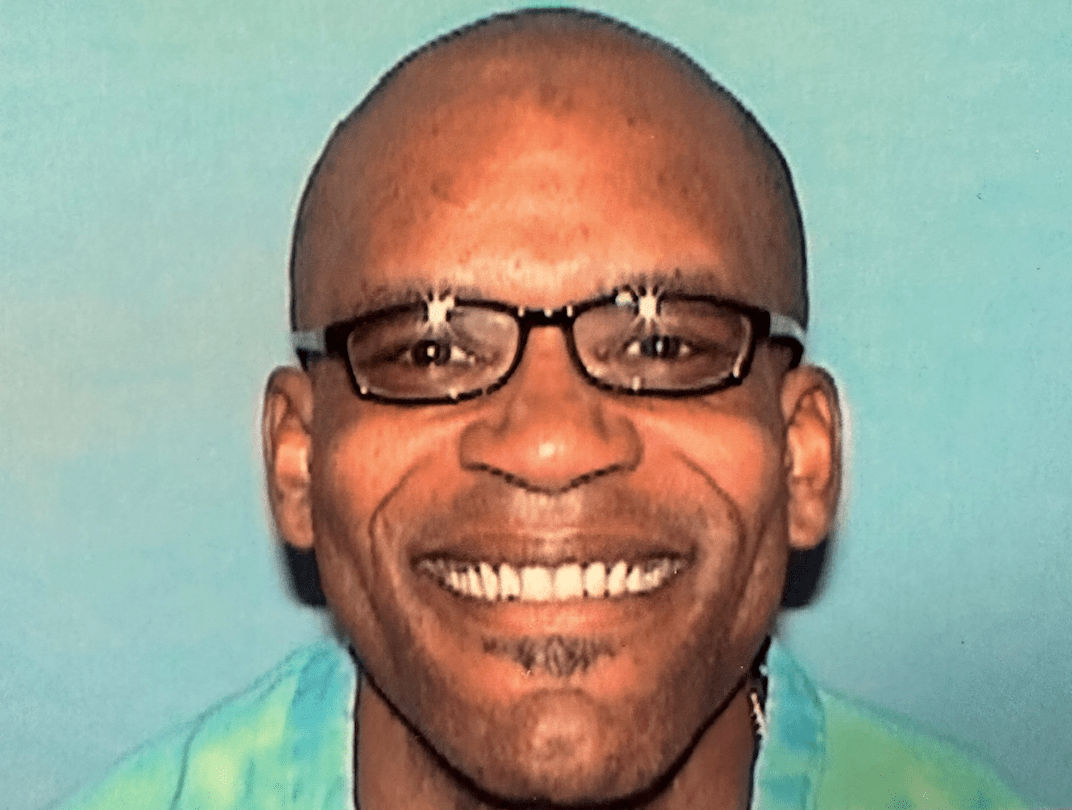

Billy Johnson, who is serving a 53-year sentence for murder and robbery at Danville Correctional Center, said that isn’t always the case.

Johnson said his concerns about access to interpreters and other tools that would help him communicate as a person who is deaf get brushed aside. One of his goals is earning his GED so that he can join a carpenter’s apprenticeship upon release, but the IDOC refuses to place him into the program, which would require an American Sign Language interpreter.

“I feel like they force me to try to feel like I’m hearing, which obviously isn’t an option for me,” said Johnson through an ASL interpreter. “I do a lot of watching and looking and wondering what’s going on.”

“All the hearing guys, they get their GED, they go to college and I’m over in the corner working hard. I’m trying to get my GED, I’m trying to go to college, but it’s not accessible to me.”

Tillie Lloyd, Johnson’s fiance, is also deaf. The 39-year-old resident of Chicago’s Riverdale neighborhood said through an interpreter that she is “very angry” about the services that are being denied to Billy on account of his disability.

“I want to see him get a better life,” Lloyd said. “I want to see him get a second chance.”