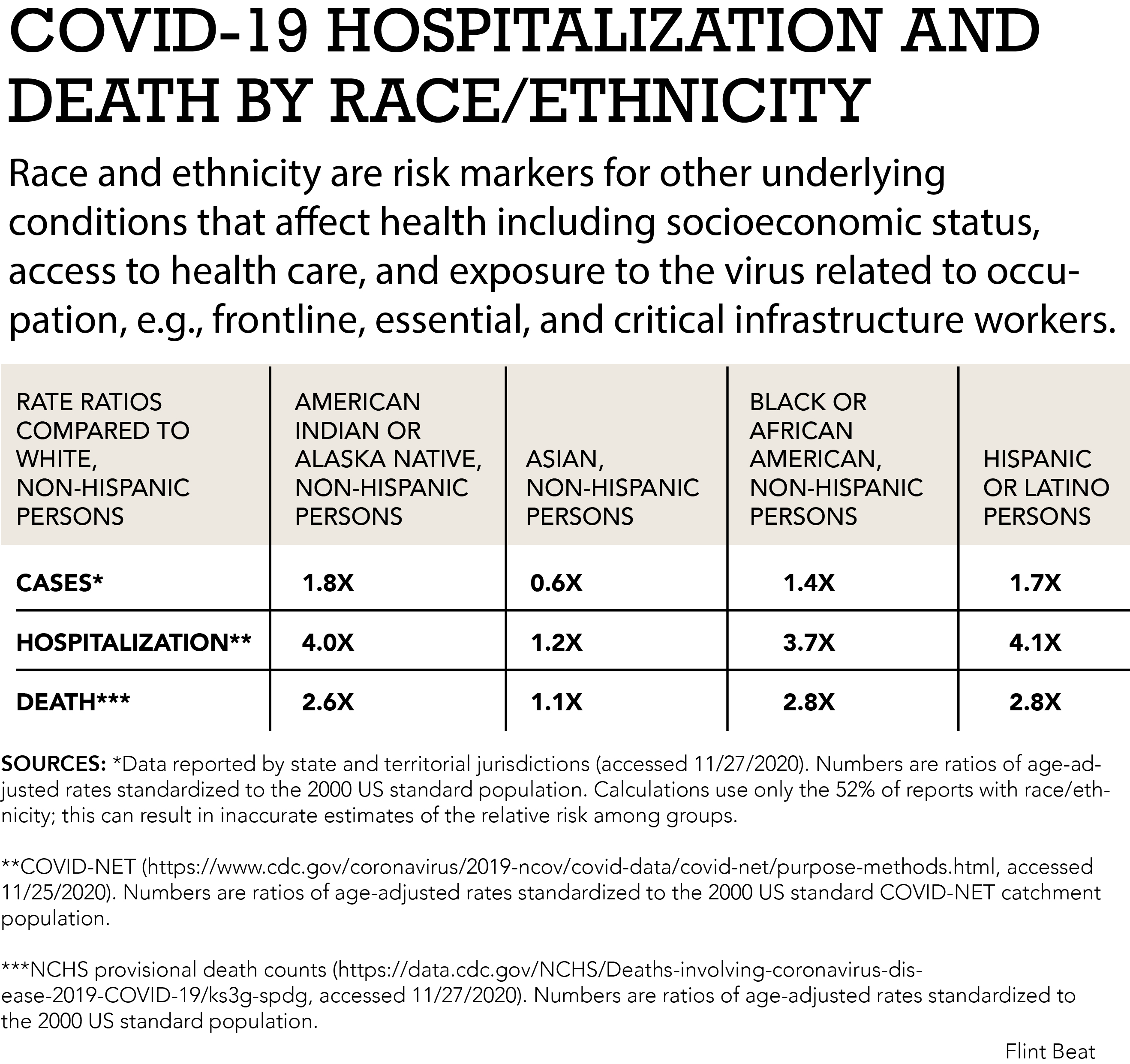

Flint, MI— If you’re Black living in the United States you’re 2.8 times more likely to die from COVID-19 compared to White and non-Hispanic persons.

You’re also 1.4 times more likely to contract the virus and 3.7 times more likely to be hospitalized, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Since the onset of the pandemic one thing has been clear: Black communities across the nation have been overrepresented in confirmed COVID-19 cases and COVID-19 related deaths.

The reasons are numerous and nuanced. People of color are at greater risk for underlying conditions that affect their health including access to health care, socioeconomic status and exposure to the virus due to holding more “frontline” or “essential” roles, according to the CDC.

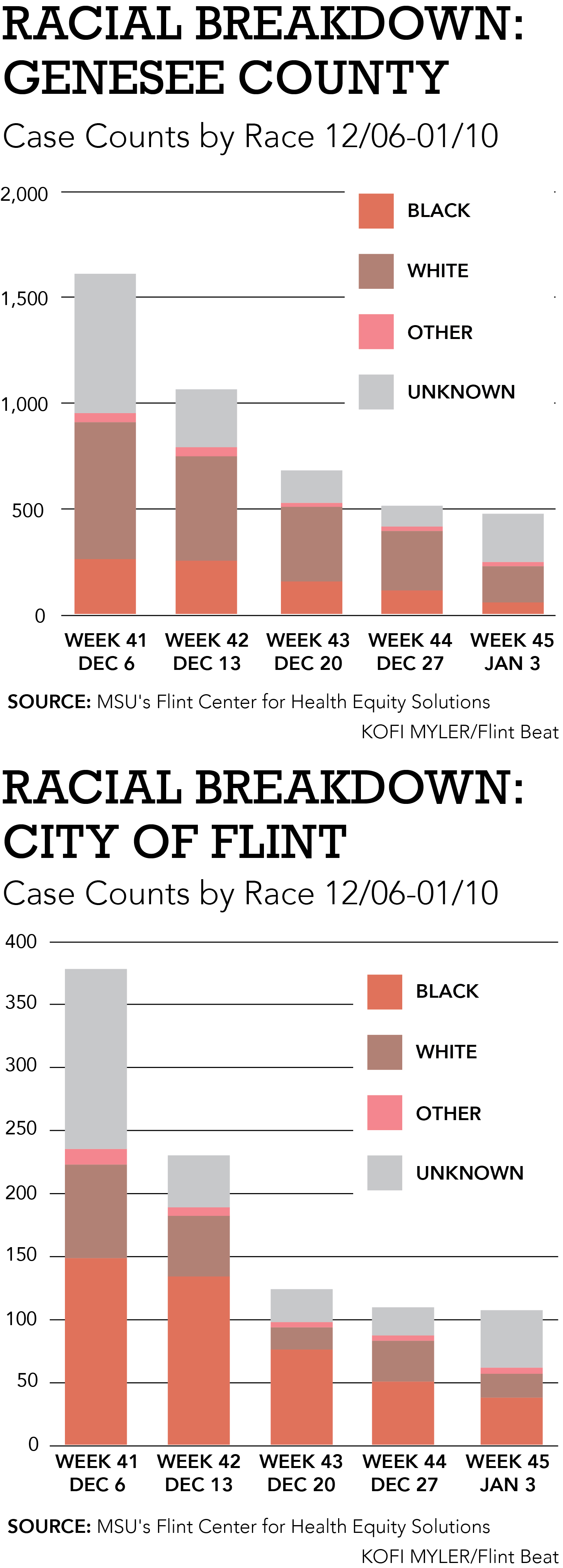

But in Flint, a city where over half of residents are Black, and throughout the rest of Michigan, health officials are seeing a new trend: infection and death rates within Black populations are dropping. This is due, officials say, thanks to statewide and local grassroots efforts to address the racial, systemic disparities that make minorities—predominately Black people—disproportionately susceptible to the coronavirus.

This shift is unique to Michigan, said Debra Furr-Holden, director of the Flint Center for Health Equity Solutions and associate dean for Public Health Integration at Michigan State University. Furr-Holden is also a member of Governor Gretchen Whitmer’s Racial Disparities Task Force, which has implemented several initiatives to address racial inequalities in Flint and Michigan.

Black residents no longer make up a disproportionate portion of COVID-19 cases and deaths.

At the start of the pandemic, Black residents represented approximately 32% of cases and 41% of deaths despite being only 14% of Michigan’s total population. Now, they represent 9% of cases and 12% of deaths. Flint’s numbers mirror the state’s in racial disparities and a decrease in COIVD-19 cases overall.

“[This is] not the case across the nation. It is an overwhelming case in the state of Michigan, specifically with African Americans. Michigan was one of the first states to transparently report on racial disparities in COVID cases. We were also one of the first states to mount a multisector statewide strategy to address the racial disparities in COVID,” Furr-Holden said.

When it comes to saving lives during a pandemic, one strategy doesn’t fit all. And in a city like Flint, where 93% of children are considered economically disadvantaged by being homeless or qualifying for free school lunches, where residents still suffer health problems from being exposed to lead-tainted water, and where food insecurity runs rampant, interventions that successfully prevent the spread of COVID-19 must target the community’s hardships and the systemic racism surrounding their circumstances.

Swiss Cheese

Preventing the spread of COVID-19, or any virus, is like layering slices of Swiss cheese on top of one another.

James T. Reason, a cognitive psychologist and professor emeritus at the University of Manchester, England developed the “Swiss cheese” model in 1990. The idea is that each prevention method, or layer, has holes so no one layer is successful on its own.

Ian M. Mackay, a virologist at University of Queensland, in Brisbane, Australia, recently took to Twitter and updated the model, adding more layers to differentiate between “personal responsibilities” and “shared responsibilities” to prevent the spread.

We have to think of it as a continuum, Furr-Holden said.

“If you start to layer all of these imperfect layers, all these pieces of Swiss cheese that have holes at different points, and you think on one end is the environment and on another end is a family, a person, community, etc.; as you start to add all the different layers, you start to build a wall of protection. But that wall of protection hinges on all these different layers that are all imperfect,” Furr-Holden said.

Public health officials in Flint and Genesee County began tracking cases early into the pandemic to identify what “layers” were missing in their efforts.

“We know exactly where all the COVID cases are, including race, sex, and then the outcome of the case whether it results in death or recovery and we’re mapping those,” Rick Sadler said, a geographer and assistant professor at the College of Human Medicine at Michigan State University.

“And so, we know exactly what the spatial temporal trends are, not just over time but by neighborhood. And so, for example, we were able to see that back in March and April, there’s a huge uptick in cases in places like Flint… And that, in part, spurred a lot of our public health action locally,” Sadler said.

Using the data, state and local health officials determined that access to testing in Flint was one layer of Swiss cheese missing from the pile.

Access to Testing

Flint resident Marty Vaughn drives a bus, but he isn’t carting kids to and from school. Inside feels more like a motorhome turned doctor’s office—and that’s exactly what it is.

Toward the rear, a sheet separates two exam rooms. Cabinets and drawers filled with medical supplies line the walls. Behind the driver’s seat where Vaughn sits, another examination table is squeezed into the corner.

The mobile unit was designed by the Genesee Health System to bring COVID-19 tests to the community. To date, doctors and nurses have performed over 1,300 tests on Flint residents.

The initiative launched in summer 2020 at a time when testing accessibility was Flint’s main concern.

“As an organization, we saw the need for testing. And one of the biggest areas for us was our group homes… So that’s why we decided to start the mobile team up and have them go out to the group homes, the shelters and the public housing units,” Executive Director of the Genesee Health System Jean Troop said.

Mobile testing allows access to Flint’s underserved, stationary populations. Health professionals can, quite literally, drive a doctor’s office to them.

“These individuals are living in situations where there’s a lot of people living with them. They have to worry more about exposure…We even did the homeless shelters in Flint…these individuals have no choice but to be where they are,” Mandi Herron said, a registered nurse and manager of GHS’ specialty health services.

It also ensures that those who do test positive receive proper medical attention.

“The first thing we make sure is that they have a primary care physician. And then [we] start making a list of everybody or every place they had contact with…and the health department follows up within 48 hours,” Troop said.

After rounds of testing, team members identified and addressed other barriers preventing these populations from getting tested.

“I think the biggest challenge is people’s fear,” Herron said. “You get people that will pull away as you tried to do a swab, or people that will just be like, ‘No I can’t do it, I’m too scared.’”

Herron said the mobile team learned to slow down, educate their patients, and ease them into the test in a comfortable way.

“Being [part of] an undeserved population plays into it. They’re not getting accurate information. They’re not able to see the news,” Herron said, adding that word of mouth, or having those share their testing experience with others helps build trust and knowledge.

However, immobile residents are only one piece of Flint’s pie, or Swiss cheese model.

Barriers

Many Flint families are “mobile,” Assistant Superintendent of Flint Schools Kevelin Jones said.

“[The inner city] has lot more issues than most people know. [They have] a lot more financial burden just to be able to live and eat. Their cell phones get cut off because they don’t have the funds and the money to support that,” Jones said.

This leads to a lot of movement as residents try to make ends meet—people change addresses or phone numbers or have neither; they might stay with one relative, and then another. The pandemic has only worsened an already precarious way of life for many.

In September, Michigan launched a barrier-free COVID testing program to address the financial burdens and hardships that bar low-income individuals from both accessing or seeking tests if they have symptoms. These hurdles include costs, transportation, having an I.D., and getting a doctor’s referral.

Three Flint churches, Word of Life Church, Bethel United Methodist Church and Macedonia Baptist Church, were selected among nine other barrier-free sites around the state.

Suzanne Cupal, community health division director for the Genesee County Health Department, coordinated efforts with the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services to bring the program to Flint.

“It’s critically important that testing be available in our community. Not only for the testing itself and identifying asymptomatic individuals but just the recognition that we need good data. Testing is really important for that,” Cupal said.

At the churches, testing is free, I.D.s and appointments are not required, and each site is equipped with interpreters for the deaf and translators for those whom English is not their first language.

One major issue for Flint residents is transportation, said Cupal, which is why the churches were selected as testing sites. “Geographically, they correlate to some of the areas that have had higher incidents of COVID-19.”

Barrier-free testing was a major game changer when it came to eliminating racial inequalities and COVID.

“[White people] already disproportionately had access to health care. They didn’t need barrier-free testing because they had primary care physicians and doctors and the ability to pay for a test. So, fixing those things, allowed the most marginalized among us to now have a fair opportunity.” Furr-Holden said.

Governmental Interference

In addition to local efforts, interventions at the state level were critical to the improvements health officials are seeing in Flint.

“What we found out in Michigan is a lot of the excess cases that we saw in African Americans were due to occupational exposure, African Americans are disproportionately overrepresented in frontline, what we now call essential worker positions, that oftentimes don’t have the kinds of provisions and protections in place,” Furr-Holden said.

In Flint, those who hold essential positions can’t follow stay-at-home orders because they can’t afford to not work. “The recommendation that people shelter in place was a bit tone deaf because it didn’t meet people where they are,” Furr-Holden said.

Enhanced unemployment benefits and Occupational Safety and Health Administration interference at the workplace helped to put protections into place. “It leveled the playing field, if you will,” she said.

The Way Forward

Recent data released by the Flint Center for Equity Solutions and the Genesee County Health Department show that total cases in Genesee County and Flint have declined for the fifth consecutive week.

“We can’t just look at the data overall, you’ve really got to look month by month to see the progress,” Furr-Holden said.

She added that while efforts to address inequalities certainly played a role in Black people being less affected by COVID, the numbers may also reflect social and political trends as well.

“The strategies that we implemented address the systematic and structural barriers to protection. Whites were less impacted by those systematic and structural barriers. They’re mostly impacted by their personal choices.” Furr-Holden said.

Personal choice, like refusing to wear a mask, might be a reason why COVID-19 cases and deaths among White individuals remain largely unchanged since the pandemic began.

“There have been more cases in the white and suburban populations than among African Americans. I think it has to do with political orientation and people’s willingness to follow basic public health guidelines. … For whatever reason, one political party decided that those things weren’t sensible and reasonable and are shoving it down their acolytes throats,” Sadler said.

More work is still ahead. While cases among Black people in Flint and Michigan are leveling out, other minorities have different structural barriers.

“We’ve moved the needle a bit on Hispanic disparities. But that wasn’t at the forefront of the efforts, because a lot of the Hispanic and Latinx community factors that contribute to the disparities are a little different…we have a lot of—I hate this word—undocumented people in our community who are members of our communities, but don’t have all of the legal paperwork in place to have their membership ratified,” Furr-Holden said. They are more apprehensive to even show up for testing because they’re afraid that they’re going to potentially at risk for deportation.”

To maintain a downward trend in racial disparities and COVID in Flint, health officials must continue to address every layer of the Swiss cheese pile. And though there is now a vaccination, it’s still only one more layer.

“The vaccine’s not going to solve all the problems, it’s just not. But it is an important layer of protection in an imperfect system,” Furr-Holden said.

Comments are closed.