Warning: This story contains descriptions of physical, sexual, and police violence.

Dear Maya, Blessed life to you and yours, always. And I pray you will have a very good day. This leaves me well. I received the book with your letter. Thank you for writing and sending the book. Your letter came as a disappointment to me. And after re-reading it, I decided the time had come for me to relieve you of our agreement for you to write about my cases. Your letter explained to me your approach to writing about me. It explains a course of writing that I'm not interested in. It isn't what I first agreed on. I thought your writing would be about my wrongful convictions in the Gibson and Ciralsky cases. Your letter impressed upon me that you plan to write something of a mini bio of my life. And that is something I'm not interested in. Yours Truly, James

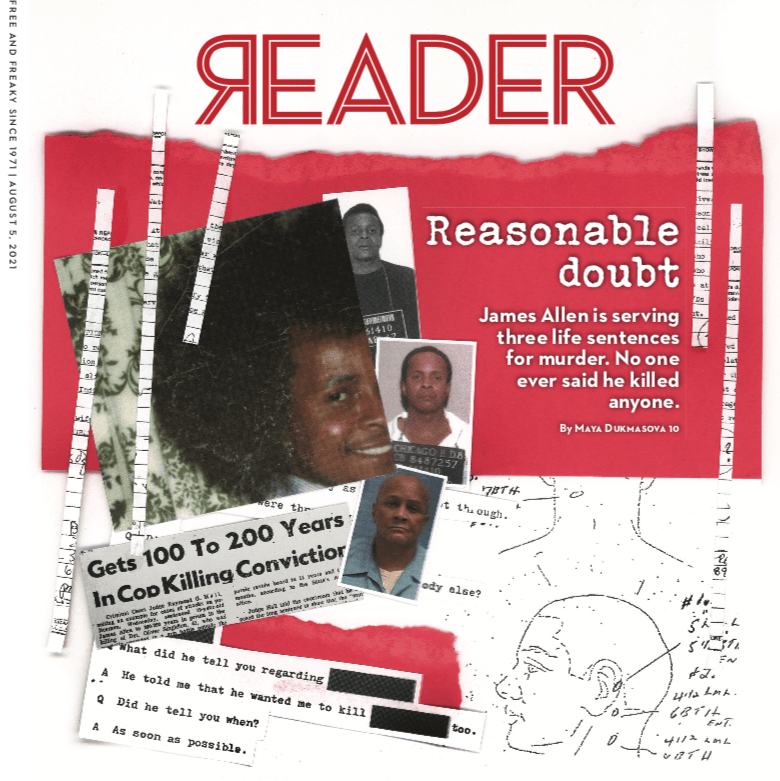

When I received this neatly penned letter it had been nearly two years since I began corresponding with James Allen, a man serving two life sentences and an additional 100-200 years in the Illinois Department of Corrections for three murder cases. Allen is one of only 30 people in the state’s prison system doing time for three or more murders. Most of the others are convicted either as serial killers or people who went on murder sprees in bouts of rage or psychosis, killing people they knew or random strangers in a series of acts (or alleged acts) that followed familiar, if shocking, trajectories. While many of their stories would be the stuff of slasher flicks or film noir, Allen’s situation, at first glance, seems like something out of a mafia movie. He was the alleged getaway driver in two murder-for-hire schemes masterminded by south-side drug trafficking kingpins—while he was on parole for a cop killing.

Rather than being disappointed, I found myself awash in relief when Allen wrote that he no longer wanted me to write about him. The book Allen mentioned was The Journalist and the Murderer, Janet Malcolm’s 1989 polemic on the emotionally dirty and morally suspect work of nonfiction writing. “Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible,” Malcolm writes. “He is a kind of confidence man, preying on people’s vanity, ignorance, or loneliness, gaining their trust and betraying them without remorse.”

My intent had been to short-circuit the dishonesty. When I sent Allen the book (which happens to take as its narrative backbone the story of a man who claims to be wrongfully convicted of murdering his wife and children), I hoped that we could have a conversation about my role in his life and his legal battle, what I could and could not promise. I thought I would eventually write something that he would consent to being published, even if he didn’t like the process I undertook to get there. But instead of helping me ease my conscience, with the letter James gave me a moral loophole.

It is “only when a subject breaks off relations with the writer,” Malcolm writes, that “the journalist is in a completely uncompromised position.” She argues that the journalist can feel free from the guilt of betrayal because an uncooperative subject doesn’t enter into the murky interpersonal dynamic masquerading as friendship that would otherwise define them. According to Malcolm, “you can’t betray someone you barely know; you can only irritate and anger him.”

This logic is, of course, as self-serving as the duplicitous “friendship” the journalist develops with a cooperative subject. Publishing a story someone doesn’t want out there is an act of betrayal even if you have no relationship to them. As a journalist, especially a white one, the way you justify it to yourself is by saying that the story is bigger than its central character, that his life experiences aren’t really just his to publicize or keep private, that they belong to everyone. This line of thinking is particularly potent when you’ve already invested significant time and energy into a story—as though with that expenditure you’ve purchased a person’s right to refuse or consent to be written about. I’d done a lot of digging by then. I decided to keep going, partially because it felt too late to turn back, and also because I believed what happened to Allen was wrong, even if I didn’t fully believe him.

In the winter of 2018 I got a note from another writer, the sort of tip you follow up on out of respect for the person who sends it. The first source is often not the most important or reliable one, but because she is first, she becomes the story’s spokesperson. Her ability to capture the journalist’s attention can make the difference between someone’s story being instantly forgotten or becoming an Oscar-winning feature.

“This guy, I know him, and he’s been locked up since 1984 for a murder that he didn’t commit,” Debbie Wilson told me in our first phone conversation. She said that after the first conviction someone had come to see Allen in prison, when he didn’t have a lawyer, and “put another murder on him that he didn’t do.” Her voice was plaintive but calm. She spoke concisely and with clear affection for the man. She told me Allen had evidence of his innocence and, after his convictions were “thrown out,” he’d done three extra years in prison because his “documents” couldn’t be found.

She hinted at a conspiracy. The authorities, she said, “keep this thing going hoping that he would just die in prison. He’s had three attacks on his life.” She made it clear that he wanted a reporter to cover his story.

Debbie’s pitch was effective. I got on Allen’s call list. Once I spoke with him directly, the actual, baroque complexity of his situation came into sharper focus. His convictions for the 1984 murders of Carl Gibson and Robert Ciralsky hadn’t actually been overturned. The Illinois Supreme Court found in 2015 that he was entitled to a rare post-conviction evidentiary hearing because another incarcerated man confessed to killing Ciralsky. He hadn’t been granted a similar hearing in the Gibson case, but he said for that murder, too, he had evidence of his innocence.

Allen’s attorney, a seasoned appellate litigator named Steven Becker, needed the original trial transcripts to prepare for the Ciralsky post-conviction hearing. But for three years the clerk of the Circuit Court of Cook County couldn’t find a box of his records in her warehouse.

I never had ambitions to investigate wrongful convictions, nor an appetite for true crime stories. But I’ve always liked to report on bureaucracy and the procedural mechanics inside legal cases—the more boring, the better. So I wrote a story about Allen’s scandalously delayed access to justice and glossed over a lot of the mind-bending details of the two murders. The story, published in May 2018, allowed me to skirt around the edges of his cases, to transmit his narrative without the burden of independently verifying the minutiae of what he said happened. It helped that much of what he told me was substantiated by extensive records collected by one of the only other people in his life—a woman named Linda, who lives on the west coast and has been his devoted advocate and friend for over a decade. Without a formal legal education, she helped Allen write many of his petitions to the court. She believed absolutely in his innocence, and had amassed thousands of pages of documents, mostly through diligent use of the Freedom of Information Act, that she shared with me. She worries about her safety as a result of her work on Allen’s behalf and asked not to be identified by her real name.

As soon as I asked questions about the lost Ciralsky case records, the clerk of the Circuit Court located them in her warehouse. The gears in the rickety local justice apparatus creaked along. Debbie called me to share how happy she and James and Linda were. And then she said something that I didn’t write down, but I remember the gist of: “James was right about you. He told me to find a young person to do this story, a young reporter would do it right.”

The comment stayed with me. After the rush of publishing the initial story dissipated, it floated back up from the depths of my mind like a drowned body inflated by decomposition. It made me suspicious of myself. In a city packed with investigative reporters who dedicated their careers to researching and writing about people railroaded by corrupt cops and prosecutors, why would a young, inexperienced journalist be Allen’s preferred choice? A young reporter would do it right.

I decided to retrace my steps.

The Pontiac Correctional Center is a maximum-security prison nearly two hours south of Chicago where the state houses 1,000 men at the cost of some $70,000 per year each. For my first meeting with Allen in 2018, Debbie and I drove down through endless fields of crops one sunny Sunday morning. She was an easy travel companion, and told me her own life story with little prompting. She’d first met Allen through a prison pen-pal program her mother ran in the 1970s. When she saw him at a court appearance it was love at first sight. Though they’d had periods of rupture through the decades, he was always her one true love. She raised her son to think of him as a father figure.

Before we entered the gates of the old prison complex, Debbie took off most of her rings and watch and Bluetooth earpiece and left them in the car, keeping on a gold chain with a small cross. We placed our keys and wallets in a metal coin locker at the drab reception area and waited for pat-downs. After a while, the guards ushered us and a handful of other visitors through courtyards and hallways, past the names and portraits of former wardens, wooden cubbies where inmates receive mail, and several heavy metal gates. In the visiting room Allen walked toward us from behind a massive steel door, bent slightly forward, wearing a uniform of a light-blue button-down tucked into dark-blue pants. He smiled warmly and gave both of us hugs, reaching over a red line on the floor. Debbie got a longer one. A guard then escorted him and the other inmates behind a glass divider. We sat on folding chairs and spoke through black plastic phone receivers. For the next four hours Allen did most of the talking. The prison didn’t allow visitors to bring in notebooks, but I tried my best to keep up and asked questions to help me remember our conversation.

Allen, then 68, was friendly and thoughtful. With his sharp nose, sparkling eyes, and easy smile, he reminded me of Harry Belafonte. He took pride in his fitness and health, and looked much younger than his age, but decades in the prison system had taken a toll on his body. He has a scar over his left eye from when a cellmate slammed a TV on his head while he slept. Touching the skin puts him in direct contact with his skull and he said he suffers from PTSD and can no longer live with cellmates. He sued IDOC over this and another attack and won; the money he got in damages pays for his attorney. Despite the violence and monotony, his mind and memory hadn’t been blunted. He had a remarkable penchant for recalling dates and was a methodical, if slightly disorganized, storyteller. He launched into anecdotes as if constantly picking up threads of an ongoing, unfinished conversation, but paused carefully through his sentences to make sure every detail sunk in. His sanity and faith in God remained intact through many bouts of solitary confinement, including more than eight consecutive years at the now-shuttered Tamms supermax prison in the southernmost tip of Illinois, where he said he made physical contact with another human being only twice, during a doctor’s examination and when receiving communion. He was moved to Tamms as soon as it opened in 1998 with the other “worst of the worst” in IDOC because he was among six inmates who pulled off the largest prison escape in state history. In 1990, with the help of a guard, they cut a 9-by-14-inch hole in a second-floor window at the Joliet penitentiary and shimmied under a fence. Allen spent 12 days on the lam before being captured in Chicago.

Allen described his youthful forays into crime as conscious choices rather than inevitable mistakes or the result of impulsiveness or carelessness brought on by abuse, neglect, substance use, or peer pressure. He said he was born into a loving home in 1950, the youngest of three children. He never went hungry or felt embarrassed for the clothes he wore to school. His parents had come to Chicago from Clarke County, Mississippi, in the late 1940s. He said his mother’s parents had been sharecroppers, but his father’s family owned 60 acres of land—rare wealth for a Black family in the Jim Crow South. Allen’s father served in WWII. After the war he got a job at the Chicago stockyards and worked long hours as a steak cutter. Allen said he was just like his father—stubborn, intelligent, a hothead with a big ego—which earned him the nickname Head. When he was about 13, Allen discovered communism. He read Marx and Lenin, but what really captured his imagination was Mao’s Little Red Book. It was the mid-1960s and he was inspired by the Black nationalist thought of Malcolm X and the Black Panthers. By 16, much to his family’s chagrin, he dropped out of school to pursue what he called “revolutionary activity.”

He painted a picture of his young self as a sort of Robin Hood. He and nine of his friends, calling themselves the Black Belt Rods, patrolled Washington Park and threatened pimps, drug dealers, numbers runners, and dice players to get off the streets between 3 and 7 PM, so kids could safely play in the neighborhood after school. He said one time they grabbed some pimps in chokeholds and used kitchen scissors to cut off their long hair. The intimidation worked. Their numbers grew to some two dozen boys, and they graduated to robbing the people they considered to be a cancer on the neighborhood. Allen said they would redistribute the money to local churches and the Black Panthers’ breakfast program. He was arrested for the first time at 17 for robbing a paperboy who he said also sold weed and ran numbers for a local racketeer. He was sentenced to seven months at the Vandalia juvenile boot camp in southern Illinois. After a few weeks he refused to shovel any more cow manure on the prison farm. He and a few other boys would soon stage a rebellion, pouring disinfectant into the cows’ trough and giving them diarrhea. Allen was transferred to Pontiac to serve the remainder of his sentence with adults.

When he got out, he and his buddies transitioned from robbing criminals to robbing companies that didn’t hire Black workers. One of Allen’s friends worked in the personnel department at Bell & Howell, a camera manufacturer in Lincolnwood, and saw that very few Black candidates were getting hired. And so in early January 1969, 19-year-old Allen and two accomplices in their 20s tracked the route of the armored truck delivering the company’s payroll and plotted a heist.

On the night of January 24, armed with tape, handcuffs, ski masks, small handguns, and an AR-15 robbed from a freight train, the three drove up to Lincolnwood in a stolen Buick for the real operation. But the armored truck never came. It turned out one of their friends had snitched. The cops had been watching them for weeks, and now, as 15 minutes passed and the crew was about to scrap the plan, a floodlight flashed onto their car. Allen said they never heard anyone yell they were police, just a gunshot and the thud of something on the door. He said he fired his rifle once, to take out the blinding light. Then, a hail of gunfire exploded from the darkness and the car rocked as bullets pierced through metal and glass. Ninety seconds later, his two friends were dead. Allen, who pressed his body to the floor of the back seat, was injured only in the buttocks.

There was a third victim. A Black police officer named Oliver Singleton was shot and paralyzed from the neck down. He survived for 11 months—long enough to testify at trial. Allen faced a slew of charges, including attempted robbery, two counts of murder for the deaths of his accomplices (what’s known as “accountability” or “felony” murder), and the attempted murder of a police officer. The state claimed that the police announced themselves and one of Allen’s accomplices shot at the cops. Allen believes that Singleton was shot by a fellow officer. Ballistics analysis showed that the officer wasn’t wounded by the AR-15 Allen had been clutching.

The Chicago Daily Defender noted the case as a “milestone” because Allen and another coconspirator who plotted the robbery were being held responsible for the deaths of their friends, even though they hadn’t killed them. The paper quoted Sam Adam, then already a prominent defense attorney, who claimed that it was “the first time a defendant has been indicted and tried for the murder of his coconspirators in the state of Illinois.”

At trial, Allen’s attorney didn’t put him on the stand and didn’t cross-examine Singleton, the state’s star witness. Allen said it was because his mother had begged the lawyer to do anything to make sure her son didn’t end up on death row, and going after a paralyzed cop testifying from a stretcher would not have won Allen any favors with the jury. “The jury stared at Singleton with shock and dismay etched deeply on their faces,” according to the Defender. “Their eyes were glued to the stretcher when attendants wheeled Singleton out of the chamber following his brief, five minute, statement.” The newspaper also noted, however, that the trial hinged on a statement Allen gave police the night of his arrest, while at the hospital without a lawyer. The judge denied his lawyer’s motion to suppress it, and when the prosecutor read it in court, “Allen shouted to Judge Philip Romiti: ‘Your honor, I refuse to sit here and listen to any more of these lies.'” After his attorney silenced him, the reporter noted:

"Allen stared at the floor and his entire demeanor changed. During the first three days of the trial, Allen was almost jubilant and a sly smile frequently creased his face. After the statement (confession) was read, however, Allen became openly hostile, glowering at the state's attorney and the bailiff assigned to guard him."

After a four-day trial and eight hours of deliberation, the jury (which included three Black women) acquitted Allen of murdering his friends, but found him guilty of the robbery charges and the attempted murder of Singleton. Less than a month later, before Allen was even sentenced, Singleton died. The state quickly indicted him for the murder of the policeman. After the second trial, the jury found Allen guilty but spared him the death penalty. He was given 100-200 years—an “indeterminate sentence.” The Defender quoted the judge telling the courtroom that it was meant to send a message that “the murder of a policeman would be considered a heinous crime.”

Allen remembered standing in front of the judge, asking if he’d ever have a chance at freedom again. The judge responded that he might if he could demonstrate he was rehabilitating. Indeterminate sentences came with a possibility of parole after about a decade in prison. The Tribune looked askance at that. Allen “won’t be locked away for the rest of his life,” the paper lamented in their short article on the sentencing hearing. “The parole laws would appear to be loaded in favor of killers.”

Allen spent his 20s in prison pursuing a slew of educational programs. He got his GED and was certified as a medical assistant, with qualifications in nursing, physical therapy, and surgical procedures. He completed a correspondence course for legal investigation and earned some credits through Joliet Junior College and Governors State University. He also spent a lot of time at the law library. In 1972 he was part of a lawsuit against the prison system for constitutional violations and unsanitary conditions in the now-shuttered Joliet prison’s “special program unit.” The SPU was segregated housing where prison authorities placed politically active inmates, gang members, and others they deemed “riot-prone” without due process. During federal court testimony in the case, Allen spoke of there being very little light in the unit, which made it impossible to read. “He had to drop out of a nearly completed correspondence course in accounting because guards took away his materials,” the Defender reported. “He said his counselor accused him of wanting to study accounting so he could ‘practice embezzlement’ when he got out.” The following year Allen helped establish a criminal law course for inmates at Pontiac. He said that he helped with the legal defense of the Pontiac 17, a group of inmates—chief among them Gangster Disciples founder Larry Hoover—charged with inciting a riot and murdering three guards in 1978. The cases against them ultimately fell apart, and Allen said his assistance earned him the respect of the Disciples and other prison gangs.

Allen didn’t just earn a good reputation with inmates. As he began petitioning the Prisoner Review Board for parole in the late 1970s, letters of support and praise came from correctional staff who worked with him at the prison hospital, State representative Peggy Smith Martin, an executive at Motorola, lawyers from the People’s Law Office (who represented the plaintiffs in the SPU lawsuit, and were the defense lawyers for the Pontiac 17), and from the board of the National Conference of Black Lawyers Community College of Law. There was even a letter of support from the president of a film production company that had interviewed Allen for “a law enforcement training film on officer survival.” The filmmaker wrote that he “exhibited genuine interest and concern for police officer survival, and was most interested in cooperating with anything that might help save a life.”

But officials from the Cook County State’s Attorney’s office and the Chicago Police Department vociferously opposed his parole. Every time Allen petitioned the board they wrote scathing letters in protest. “He has been a threat to society all his adult life and culminated his criminal activity by brutally murdering a Chicago police officer,” State’s Attorney Bernard Carey wrote in 1978. “It is the policy of this Office to vigorously prosecute police killers,” he later wrote, and “to strongly oppose the parole of that type of felon.” In 1979, CPD’s acting superintendent wrote that the “vicious, wanton action of Allen in fatally wounding Detective Singleton while in the process of attempting to commit an armed robbery clearly indicates that he is a menace to society.” It seemed to matter little that it was a fellow officer, not Allen, who had apparently shot Singleton.

Year after year he was denied parole until finally, in April 1983, the Prisoner Review Board agreed to let him out. Allen, then 33, was sent back to Chicago with the help of letters from people eager to employ him, and community petitions vouching for his good character. He was released to live in a South Shore apartment with his fiancée, Denise Mims, under strict supervision from a parole officer.

In a letter to me, Allen described the transition to parole after more than 14 years behind bars. He wrote that the day before he left Stateville, Disciples leader Hoover “offered me money to avoid returning to prison for committing a crime of finance.” Other gang leaders did the same “in appreciation for my role in the defense of those gang leaders and members that were indicted” for the Pontiac riot. “I knew before the parole board released me that money from gangs would be available for me,” he wrote. He maintains, however, that he has never actually been part of any gang, and no prison or court record I’ve seen has shown otherwise. “I came to prison in October 1970 as a non-gang member, and I left prison April 13, 1983 a non-gang member. And for that gang leaders honored and respected me.”

He also wrote that his relatives and friends, “and quite frankly, people I did not know,” took up a collection of money and clothing on his behalf. He got a welcome home party, and soon after permission from his parole officer to travel to Mississippi to see his parents, who’d moved back in the time he was away. He said his father and paternal grandmother gave him $5,000 and bought him a new green Volvo with velvet upholstery. The “economic support” he received didn’t just take the form of cash and gifts. “In the first week of June 1983 in my hands I had over $1,300 in food stamps,” he wrote, describing in vivid detail how an old friend brought him five intact booklets in a little white bag. “I had so many food stamps I started giving food stamps to my neighbors.”

Still, Allen said he wanted to work. He said he tried a job at the People’s Law Office, but he didn’t last long enough to even draw a paycheck. He recalled that police officers would follow him to the office and harass him and that he and the lawyers came to an agreement that it was better for them to part ways. Jeffrey Haas, one of the People’s Law Office attorneys who’d written to the parole board that he was eager to employ Allen, had only the vaguest recollection of him more than 40 years later, but said it was plausible that Allen and the office were drawing a lot of unwanted attention from the police. Allen said after the PLO he tried and failed to get a job in the medical field. Finally, his dad was able to secure him a job with a lumber company in Mississippi, but the parole board didn’t approve Allen’s request to transfer out of state.

Allen said he faced regular surveillance and harassment from Chicago police officers who he said would show up in front of his house, follow him as he ran errands, and even arrest him periodically on bogus charges. In June 1984 he was arrested for illegally having a gun; he recalled being pulled by cops from the back of a cab and watching them extract a pistol from underneath one of the seats. The charges were dropped the first day he went to court. Allen took short trips to Mississippi as frequently as possible, and his mother, sister, and other relatives visited him in Chicago. He took his nieces and nephews and Mims’s son to Six Flags Great America with the permission of his parole officer. He played basketball, read books, and went to the movies, but though he was happy to be free, he described feeling unsafe and uncomfortable in a city that had changed a lot since he was 19.

He recalled that the conditions of the Washington Park neighborhood he knew growing up were “truly shocking . . . To see men and women in 1983 that I had worked closely with in the 60s, doing the very same things we had fought against to rid our hoods of was painful to my heart and mind.” He was disturbed by the ubiquity of drugs. The streets were worse than when he went away. “I cursed the parole board for not considering my request to be granted parole release to Mississippi.”

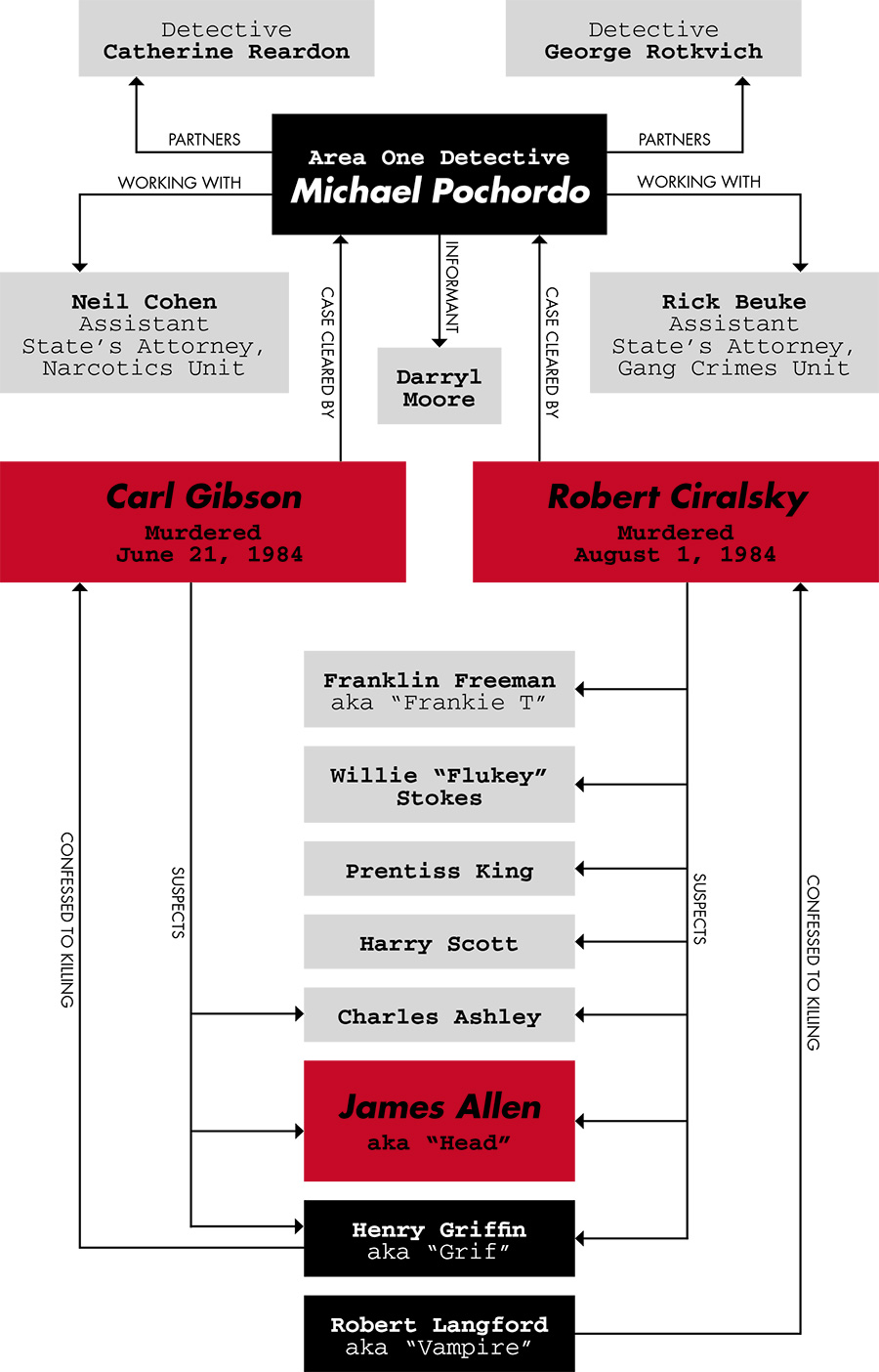

Seventeen months later, on August 9, 1984, Allen returned to his apartment with the paperwork to take another trip to Mississippi in his breast pocket. He found a swarm of police officers. His apartment was ransacked. His sister, fiancée, and their kids were confused and in tears. Allen saw a tall, corpulent detective in his living-room mirror as the officers handcuffed him. He said the detective—Michael Pochordo—squeezed in next to him in the back seat of a squad car and elbowed him in the chest every time they hit a bump on their ride to the precinct. Within a couple of days he was charged with the murder of Carl Gibson, who police said was shot in a car Allen was driving and dumped on an exit ramp off the Chicago Skyway. Later, he’d be charged with being the getaway driver in the murder of Robert Ciralsky, which happened a week before his arrest.

There are two stories about what happened next and which one you believe depends on who you see as credible, and on how the impression of credibility builds in your mind based on your own beliefs, biases, and experiences. Did the state successfully bust James “Head” Allen, a sly hit man, for two murders he dared to participate in while on parole? Or did they successfully railroad him simply for being a paroled “cop killer”? Over the course of two years I puzzled over more than 4,000 pages of police and court documents, spoke with dozens of sources, and pondered his cases from every angle. The investigation left me with some unanswered questions about James Allen. But, more significantly, it left me questioning what journalists expect from people who claim to be abused by the state.

I’m writing this story at a time when the minds of an increasing number of people with no direct experience of police misconduct and prosecutorial overreach have stretched to accept that cops do hurt, torture, and kill people; prosecutors do build cases on false testimony, false confessions, and a total lack of evidence; and America’s law enforcement and criminal punishment systems are rife with violations of both the Constitution and basic human dignity. And yet, commonly held conceptions about the people on the receiving end of these injustices remain pretty rigid, and journalists help reinforce that. We may have made some progress since the New York Times proclaimed that Michael Brown was “no angel,” but we still prefer to focus our coverage on victims of state violence who are unarmed, docile, and simple. We may not expect them to be innocent, but we expect them to be truthful and straightforward. We demand they establish their credibility by submitting themselves to scrutiny of their deepest wounds, patiently letting us poke them to see if they bleed, hiding nothing about themselves and satisfying our every curiosity. Doubt creeps in when they draw boundaries, perform, lie to make themselves appear better than they are. Doubt creeps in, in other words, when self-proclaimed victims of state violence act not as suffering and repentant martyrs but exactly the way we all do when we feel we’re being evaluated. It seems that no matter how often we see the state cheat to win criminal cases with the help of deception, violence, junk science, and cascades of cognitive biases, it’s still the state that is more likely to enter our mental courtroom with the presumption of innocence.

In one of her many dense and lengthy e-mails to me about Allen’s situation, which sometimes came with explanatory cartoon animations that she designed herself, his friend Linda wrote that I was looking at the cases “the way I was in the beginning—in terms of what doesn’t make sense.” She said that eventually she had a “mind shift” that made her see things differently. “There are two crimes. One is the murder . . . and one is the frame job.” If Malcolm is right that “what gives journalism its authenticity and vitality is the tension between the subject’s blind self-absorption and the journalist’s skepticism,” what would it mean to direct the skepticism we reflexively have for convicts toward the state?

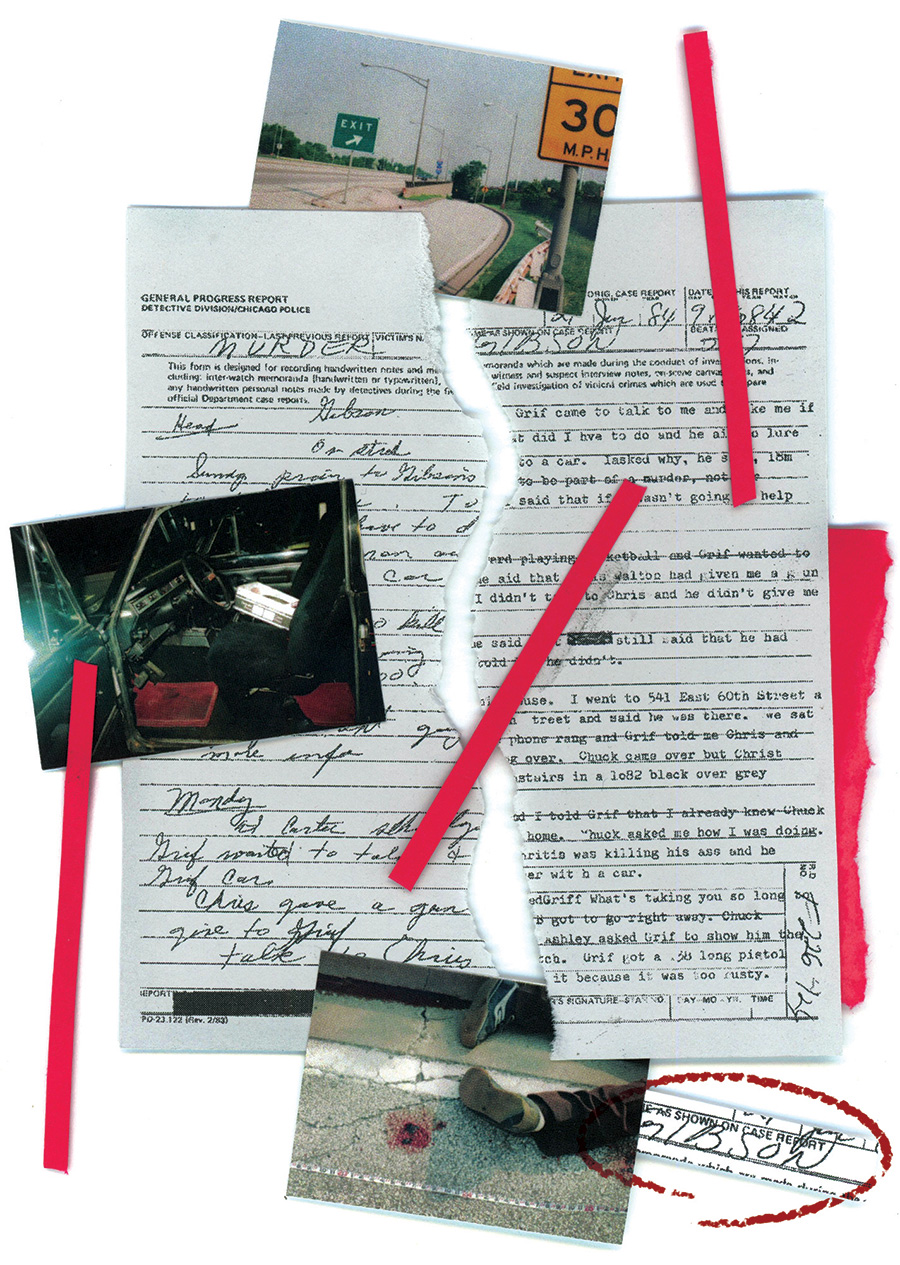

On the morning of June 21, 1984, police arrived on the 73rd Street exit ramp off the Chicago Skyway to examine the body of a bearded, chubby, Black man. Thirty-eight-year-old Carl Gibson was found lying facedown next to the curb about halfway down the ramp, wearing a black leather jacket and cheap black sneakers. A blue bandanna was hanging out of the back pocket of his pleated brown pants. His white shirt was soaked with blood. He wore a wedding band and a thin gold chain around his neck. He was found with his ID on him, a welfare card, and a copy of a recent criminal complaint charging him with selling drugs.

Four bullets had been fired at his left ear and neck, at least one of them from less than a foot away. There were two bullets lodged in Gibson’s head (inside the ear and at the base of his skull) and two exit wounds on the right side of his face. One of the bullets had torn through his spinal cord, one through his throat. The medical examiner also noted “chronic needle marks” on Gibson’s forearms but the toxicological report came back negative for alcohol, opiates, and barbiturates. Gibson’s last meal was likely a cheeseburger. “An obese and young appearing male was gunned down on the exit ramp,” the report summarized.

No bullets were found on the exit ramp near the body, but the blood on the scene suggested a story of movement. There were two trails—a short one close to the ramp’s juncture with 73rd Street, and a longer one which flowed from Gibson’s body. No reports confirm that the disconnected, shorter trail of blood belonged to Gibson, but in one of the first media accounts of the case the Tribune reported that Area One detectives believed Gibson to have been shot near the bottom of the ramp. Gibson’s head pointed upward, as if he’d been walking or running up toward the Skyway when he collapsed from the bullet that hit his spine.

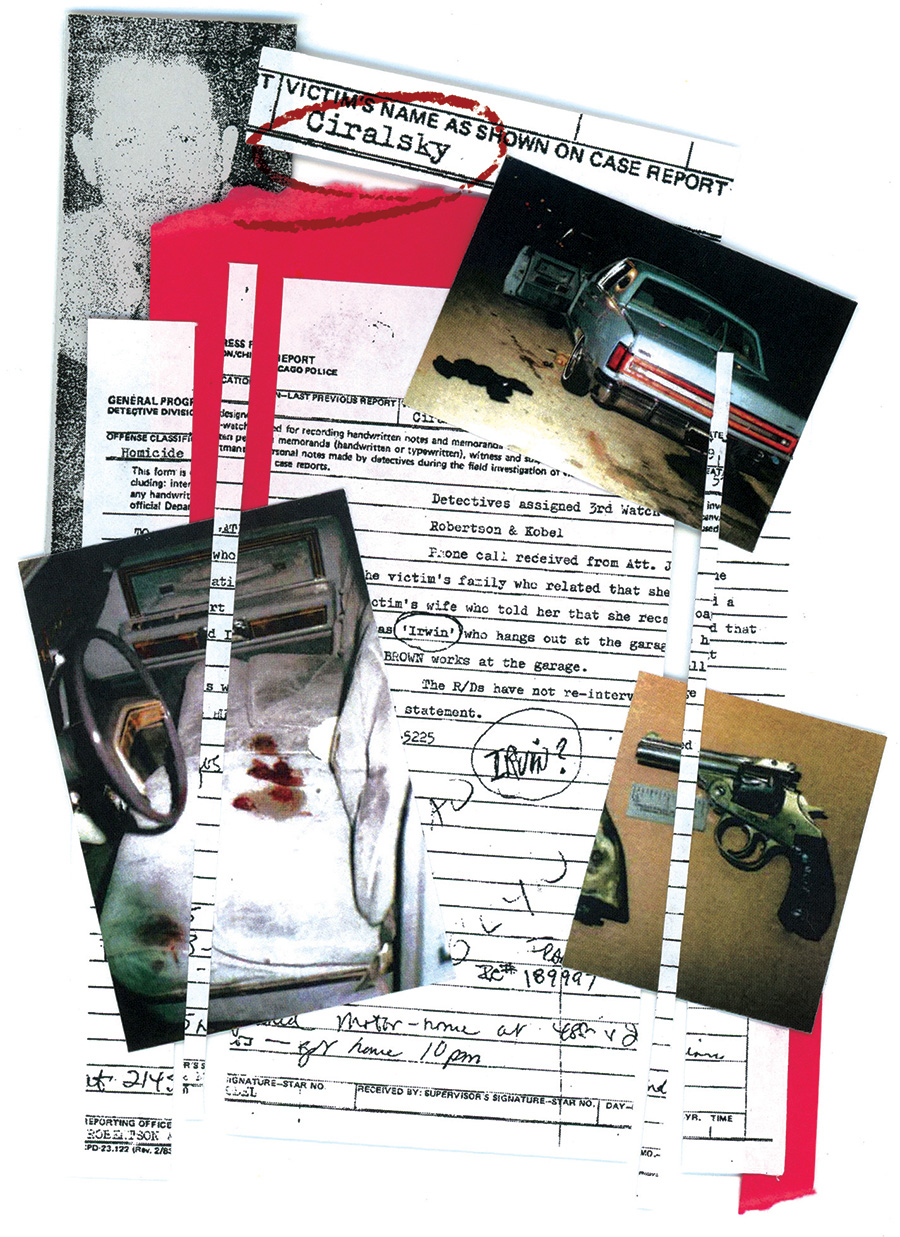

The narrative of the police investigation over the course of the next six weeks is based on a review of CPD detectives’ “General Progress Reports”—mostly handwritten notes produced while working out on the street—and “Supplementary Reports”—typewritten summaries of investigative work filed after every day or two. This narrative may not reflect reality (because the department may not have shared all existing records in response to FOIA requests or subpoenas, because the cops could make up interview notes, because interviewees could be lying or wrong) and it may not even reflect the “facts.” But the documents do tell a story that’s worth remembering as one considers how James Allen came to be accused of being involved in Gibson’s murder.

The first notes made on June 22 by the Area One detectives assigned to the case, John Robertson and Richard Kobel, were brief: “Victim shot for unknown reasons at this time. It should be noted the victim was involved in drug traffic in the area of 65th and Cottage Grove.” One person interviewed said he saw Gibson drinking on the street around 9 PM the previous night. Gibson’s girlfriend told the cops that he walked her home around 9:30 PM, which Sherman Overstreet, “a known dope distributor” in police custody, corroborated.

Both Gibson and Overstreet worked for 66-year-old Charles Ashley, the central target of “Operation Camelot,” a months-long probe into his alleged narcotics operation. A few days before Gibson was killed, both men were arrested during a raid on one of Ashley’s drug houses. The day Gibson’s body was discovered, Overstreet checked into the Cook County State’s Attorney’s witness protection program. The detectives’ first theory was that Gibson was killed because Ashley wanted “to silence any potential witnesses against him.”

The next investigative report was filed on July 2. Detectives Robertson and Kobel had identified potential suspects: Richard “Dog” Wallace and George “Lookie” Lewis, who were usually together and riding around in a small black van, according to a confidential informant. The informant said that two days before the murder Dog was seen with Ashley, and that on the night of the murder Gibson was seen entering the black van to join “two unknown male blacks.”

A week later the detectives interviewed Ashley. He said he didn’t know anything about the killing, but that he’d seen Gibson talking to someone he knew to be a cop two or three times a week for “a couple of months.” He mentioned that Gibson had a beef with someone named “Bull.” Ashley also wanted to know whether detectives had made any progress on investigating the armed robbery he’d reported a few days earlier, when he was attacked in an alley behind his home.

On July 11, Robertson and Kobel interviewed Dog, who told them he’d learned about the Gibson homicide from the Sun-Times. He said he didn’t own a car or have a driver’s license or know anyone with a black van. Dog’s lawyer objected to him answering questions about where he was the night of the murder, but Dog agreed to take a polygraph on the condition that his lawyer be allowed to see the questions beforehand. No more records related to this investigation were produced for nearly a month. Dog, Lookie, and Bull were never mentioned again in any records related to the Gibson murder.

On Wednesday, August 1, Area One got hit with another homicide. This one happened in Hyde Park on the 4800 block of Kimbark—a leafy street lined by sprawling, historic homes. The basic facts, per the first police report: Robert Ciralsky, the 60-year-old white owner of a drug and liquor store on 58th and Indiana in Washington Park, was accosted by two Black men as he was getting out of his car in front of his home around 11 PM. Ciralsky’s wife Paula and 14-year-old son Robert Jr. heard two shots that brought them to the window. The boy grabbed a gun and saw the men standing over his father’s body, which was sprawled in the front seat of his light-blue Lincoln. He yelled at them to freeze and fired a shot, which sent them running. Ciralsky died within the hour. The autopsy would later confirm that he succumbed to gunshots to the forehead and shoulder, which pierced his brain and lungs and left medium-caliber bullets lodged in his tissues. Among his personal possessions were tan slacks with a torn left pocket, an address book, some jewelry, and a wallet.

When interviewed by detectives Brian Regan and Steve Glynn that night, Ciralsky’s wife, son, and son-in-law (who worked at his store) confirmed that he would take home cash from the register when he closed his shop, usually in a rubber-banded roll that he carried in his left pocket. The family believed that such a roll with up to $1,500 was missing. The detectives noted that Ciralsky was “apparently shot during the course of an armed robbery” by assailants who either followed him home from the store or were waiting for him to arrive.

Several neighbors were interviewed about the killing. Two of them said that they saw two Black individuals inside an unfamiliar brown car (perhaps a Camaro) with California plates idling with the lights off on the corner just north of Ciralsky’s house shortly before the incident. Three others saw a dark-colored car speeding off after shots were fired, driving north in reverse on Kimbark, and then east on 48th. No one could describe the assailants.

Detectives also interviewed the last people who saw Ciralsky alive—John Dorbin, who’d worked for Ciralsky for the last 30 years, and a CPD sergeant named James Moran who’d been friendly with the shopkeeper. Dorbin said he and Ciralsky closed up the store and as they left, Moran had pulled up and Ciralsky stopped to chat. Dorbin and Ciralsky both got in their cars and drove north on Indiana; Dorbin didn’t see anyone following Ciralsky home. He told the cops that Ciralsky was fearful of assailants—in 1958 he had shot and killed three men attempting to rob his store in one week—and used to carry a gun home with him “but had stopped the practice after being arrested several times for the gun.”

The day after the murder, Paula Ciralsky told detectives that a few hours after her husband was killed she received a call from someone “she described as a [Black woman] with a southern accent.” The woman asked to speak to her son, calling him Robbie—a name only family and friends used with Robert Jr. When she told the woman that her son was sleeping, “this woman then stated, ‘If he could shoot at them then he is a witness,'” and hung up. The detectives noted that Paula immediately hired a security guard for the house.

Two days later, Area One detectives Robertson and Kobel (who had been working the Gibson homicide) filed a report after another conversation with Paula. She said that the money her husband’s shop made the night of the murder was found safe in the cash register, meaning he probably had no roll of cash in his pocket—the new theory was that nothing had been stolen. “Apparently the offenders were interrupted in their robbery attempt,” the detectives concluded.

The widow provided one more piece of information to detectives at the end of August. The Ciralskys’ estate attorney contacted Area One to relay that Paula had come to recall that one of the two assailants looked like a man called “Irwin” who “hangs out at the garage at 48th and Indiana.” Despite this new lead on a potential suspect, after that tip the murder investigation went cold.

The big break in the Gibson case arrived unexpectedly between August 5 and August 7. Area One Detective Michael Pochordo—who until then hadn’t been involved in the investigation—said he received a phone call from Darryl Moore. Moore, who would later testify that he did “enforcing” for Charles Ashley, was locked up on narcotics and weapons charges at the Cook County Jail. He told the detective he had information about the Gibson killing.

In a sworn affidavit to a judge, Pochordo claimed he’d known Moore for four years and that Moore had provided him with relevant and accurate information on ten other homicide investigations, which resulted in six convictions. Pochordo said Moore told him that Ashley first offered him $2,300 and three ounces of cocaine to kill Gibson. When Moore refused, Ashley told him he would ask Henry Griffin and James Allen to do it. Moore said that Griffin and Allen told him a few days later that they’d accepted the contract and that Griffin showed Moore a .38-caliber revolver he intended to use. Moore also said Allen showed him an ice pick that he would use to help kill Gibson.

Not only did the alleged killers apprise Moore of their plan and show him their weapons, but they also told him it was an “easy contract” when he saw them a couple of days after the murder. Moore said they told him they were now searching for Ashley to get paid and that Allen threatened to kill Ashley if they didn’t get their money. Allen allegedly said he’d made a tape recording of the discussion they’d had with Ashley about the contract and that the tape would be sent to the cops if the “old man” crossed him.

Pochordo wrote in the warrant affidavit that, according to Moore, Allen and Griffin were driving in Griffin’s black Chevy truck with wide gray stripes on the sides when he saw them before and after the murder. The detective cited earlier police reports about Gibson being seen entering “a black van” with two Black men on the night he was killed. But he didn’t mention that the confidential informant who observed this said the men in the van were Richard “Dog” Wallace and George “Lookie” Lewis.

A judge approved the search and arrest warrants against all three suspects, in addition to a wiretap warrant for Griffin, whom Moore claimed he could engage in further conversation about the murder over the phone. The next afternoon all three men were arrested. Allen was taken from his South Shore apartment, Ashley was pulled over in Hyde Park, and Griffin was confronted by police while naked on the toilet in his nephew’s Washington Park apartment. Along with him, police also arrested two women, Velores Brooks and Evon Knox, and recovered two guns (a .32 and a .38), 99 credit cards, 53 personal identification documents, and six driver’s licenses belonging to other people.

It’s difficult to piece together what exactly happened inside Area One headquarters at 51st and Wentworth after these arrests. Chicago police and prosecutors didn’t make video or audio recordings of interrogations in the 1980s. Arrestees frequently weren’t given an opportunity to call a lawyer. Black and Latinx suspects sometimes disappeared in CPD stations for many hours and emerged bruised, bloodied, even electrocuted, having confessed to all manner of crimes.

The statement that would prove to be the linchpin in Allen’s case for the next 35 years was dated the day of his arrest and signed by Pochordo’s partner, Catherine Reardon. Though Allen has never claimed that he was physically mistreated at Area One, he maintains that this police report about what he said was fabricated. In essence, the statement is a confession—not to knowing participation in the murder, but to being there when it happened.

Reardon’s notes on the statement appear on several pages of a CPD “General Progress Report” notepad. Unlike every GPR produced on this case until that point, the space where a supervisor’s signature is supposed to appear is blank. The first four pages are shorthand notes in wide scrawl, but subsequent pages are a highly detailed, typewritten narrative. Here’s the story attributed to “Head”:

Allen said that a few days before Gibson was killed, Griffin approached him and asked if he wanted to split $5,000 in exchange for helping him lure some man out of a building who Griffin would then kill. Allen said he wasn’t interested in being part of a murder, especially not for $2,500. He also asked why the man was being killed, but Griffin refused to tell him more. The next day Griffin approached Allen as he was playing basketball and said that a man named Chris Walton had told him that he’d given Allen a gun to pass on to him. “I told Grif that I didn’t talk to Chris and he didn’t give me any gun,” Allen said.

The night of the murder, Griffin had invited Allen to his home. Charles Ashley phoned and then came over. Allen said he remembered Ashley from before he went to prison and remarked that “it looked like his arthritis was killing his ass.” Allen overheard Ashley asking why it was taking Griffin so long to “kill the two sons of bitches.” Allen said that Ashley was referring to his own brother, who’d assaulted him a few days before that, and “the snitch.” Ashley also wanted to see which gun Griffin would use on “the snitch,” and said the pistol Griffin showed him was too rusty. He gave Griffin $200 in $50 bills and told him to buy a different one. “I want that son of a bitch dead before the morning,” Ashley said, according to Allen.

After that, Allen rode with Griffin to Chris Walton’s place. Walton clarified that he’d given a gun to someone else to pass on to Griffin, not Allen, saying, “This ain’t the Head I’m talking about—I’m talking about Muscle Head.” Darryl Moore was also at Walton’s place, and Allen said he showed Griffin a couple of guns, though he never actually saw any weapons change hands. Griffin and Allen soon went back to Griffin’s house, picked up three of his relatives, and drove them to a game room at 93rd and Stony Island. Allen stayed in the car and Griffin went inside the building with the three relatives. He came out shortly after with only one person, whom he introduced to Allen as Carl. Griffin asked Allen to drive his car and sat in the back seat, which Allen said was “unusual.” Carl rode shotgun. “I knew something was wrong,” Allen said. Griffin told him to drive to 90th and Saginaw to get five pounds of quinine that “Doc” Ciralsky had sold to Ashley. (“He sold quinine and stuff for mixing up dope,” Allen explained to the cops about Ciralsky, whose murder their colleagues at Area One had already been investigating for more than a week.) Then Griffin told Allen to take the Skyway back to their neighborhood.

As Allen drove north on the Skyway and they approached the 73rd Street exit, “three or four loud shots rung out. That’s when I [dis]covered Grif had shot Carl in the back of the head . . . Carl had slumped over, the blood was all over the car.” Allen said he pulled the car over on the exit ramp, his ears ringing. He jumped out and Griffin pointed the gun at him and shouted to get back in the car. Allen said he took off running and didn’t stop until he reached his home about two miles away.

After the murder, Allen said Griffin made several more threats against him and that to protect himself, he recorded an audiotape describing what happened so that he could turn it over to the police. After learning about the tape, Griffin and Ashley approached him several times about buying it from him.

Reardon’s typewritten narrative breaks here. But it’s possible to glean the next part of Allen’s story, because it was summarized in two other documents: a formal, typed Supplementary Report Pochordo and Reardon filed to clear and close the case, and an undated memo Cook County assistant state’s attorney Neil Cohen wrote to his boss Kenneth Wadas. Cohen was a leading prosecutor in “Operation Camelot” and had been working for months to build a case against Ashley. In his memo, Cohen wrote that after Allen was arrested and brought to Area One, Allen actually spoke to him first, one-on-one, then agreed for Pochordo and Reardon to enter the room and repeated “substantially the same statement.” Here’s how the story Allen allegedly told them ends, according to Cohen’s memo:

Sometime in July, Ashley and Griffin cornered Allen and he got into Ashley’s car. During the conversation, Ashley asked Allen to pull a tire iron out from underneath the front passenger seat where he was sitting. The object was actually a gun. As Griffin menaced Allen with a .45 automatic from the back seat, Ashley told Allen to hold the gun like he was going to shoot and to really press his fingers into the metal. With Allen’s prints on the gun, Ashley had him drop it into a ziplock bag. Ashley then waved over a man whom Allen recognized as a CPD detective and gave him the bag with the gun. The detective also looked at Allen’s ID and told him that if the gun was used in a crime he’d be arrested for it. Allen said that on August 3, Griffin called him and said that Ciralsky had been killed. Allen’s prints were “on the gun that did the killing.”

There are many strange things about the form and content of Allen’s statement, which, according to Cohen and the Area One detectives, he gave totally voluntarily, without the presence of a lawyer, and almost without prompting even though he never signed the statement, or wrote anything himself, or agreed to go on the record with a court reporter. Allen had had significant experience with the criminal legal system—indeed his convictions related to the 1969 heist attempt hinged on statements he made to the cops after his arrest without a lawyer present. He’d been part of constitutional lawsuits against the Department of Corrections, was certified as a legal investigator, was presumably as well-versed on his rights as any criminal suspect could be. And yet he apparently spoke openly to law enforcement officials after being arrested for murder and even signed a waiver of his rights about an hour and a half after the interview concluded. Not only did Allen confess to being present during Gibson’s murder, but he also volunteered information that could tie him to the murder of Ciralsky.

Reardon’s handwritten notes on Allen’s story sprawl across the wide-ruled GPR pad in a mess of abbreviations and incomplete sentences. On the last of the handwritten pages, a second, distinct handwriting appears next to Reardon’s. It’s angular and thin and slanted, and captures details of the story as though two people listening only had one piece of paper to take notes on. The pages that follow are typed and remarkable not only for their level of narrative detail, but for their fidelity to speech pattern. Both the handwritten notes and the typed notes start at the beginning of the story—as though the statement was first noted by hand and then retyped. A handwritten sentence such as “Told him it looked like his arthritis was killing him,” becomes “I told Chuck that it looked like his arthritis was killing his ass,” in the typed version. It seems likely that the handwritten notes were taken down as someone was speaking. But the typed ones—unless Reardon had a prodigious ability to recall subjects’ speech patterns or a tendency to embellish on her notes—read like they were transcribed from an audio recording. However, there is no record of Allen ever being recorded at the police station. He told me he never saw a recording device in the interview room (and besides, he said he never made any statement to Pochordo or Reardon).

Michael Pochordo died in 2017. He and several other Area One detectives stand accused in a pending federal lawsuit of manipulating a lineup and coercing a false confession to an arson out of 14-year-old Adam Gray in 1993. Gray was sentenced to life in prison for murder but was exonerated after more than two decades behind bars. I wrote a letter to Catherine Reardon, including a copy of her GPR and asking to talk about how murder investigations were conducted at Area One. She wrote back that she wasn’t comfortable discussing old homicide cases. She later declined an opportunity to respond over the phone. None of the other detectives and sergeants who worked at Area One with Pochordo and Reardon and are still alive returned my phone calls.

I showed the GPR to Bill Dorsch, a retired detective who worked at Area Five in the 1980s and was instrumental in exposing the corruption and abuses of his colleague Reynaldo Guevara.

“All I did was homicides, I don’t recall anyone even having a tape recorder,” Dorsch said. “They’re putting everything from verbal conversation into handwritten notes,” he said, describing detectives’ typical interview procedures. “You use the GPRs to enhance your memory of what you learned. It wouldn’t be unusual to add to the notes, but it’s usually done in the Supplementary Report and not in a typed GPR.” Though Dorsch said it’s possible that a detective might take some “literary license” in depicting how an interviewee speaks, he found it strange that it would extend to information that had nothing to do with the matter at hand—such as remarking on someone’s arthritis.

The lack of a supervisor’s signature on the report also raised red flags, especially given the fact that this was a murder case involving a high-profile target like Ashley and the suspect being interviewed was a paroled “cop killer” arrested on a warrant. “I can’t understand why a sergeant wouldn’t sign” a report that represented a crucial breakthrough in a big investigation “unless the sergeant knew something was wrong and didn’t want to put his name to it,” Dorsch said. He concluded that the handwritten interview notes were likely “enhanced at a later date” with the typewritten pages. “There’s no proof of when the report was written,” he said. “They could have gone back after the handwritten GPRs and decided, ‘We gotta make this better than it is.'”

Steven Drizin, a false confession expert and codirector of Northwestern University’s Center on Wrongful Convictions, also found the GPR strange and said it was unusual that it was typed. Drizin confirmed that CPD didn’t make recordings of interviews or interrogations in the 1980s. I also spoke to Andrea Lyon, a distinguished defense attorney with a long track record of acquittals in death penalty cases. Lyon was a public defender through the 1980s and handled many cases out of Area One. She had only the vaguest recollection of Pochordo as a detective with a reputation “for having done a lot of dirt,” but she’d encountered Reardon several times. Lyon recalled that when Area One cases got to court, Reardon would often be the one testifying to confirm that the defendant confessed to the crime and denying that there was any coercion. “Reardon would play this role, like, ‘I was there and I took notes and I know what happened,'” Lyon said. “It kind of got to be a joke in our office, like, ‘Oh Reardon took notes? Then someone confessed.'”

Allen’s story as it appears in Reardon’s GPR, her and Pochordo’s final Supplementary Report, and Cohen’s memo to his boss contains a few noteworthy differences. For example, Chris Walton and the story of a gun and a mix-up between “Head” and “Muscle Head” is missing in the Supplementary Report and Cohen’s memo. Cohen also writes that Allen said he didn’t stop to pick up quinine from 90th and Saginaw. In the cops’ reports Allen doesn’t mention anything about getting on the Skyway southbound and then making a U-turn to go north. While Cohen notes in his memo that Allen signed a waiver of his rights after speaking to him and the detectives, the detectives wrote in their Supplementary Report that Allen signed the waiver before making his statement.

The portion of the story about a gun with Allen’s fingerprints on it being given to a cop and then being used to kill Ciralsky was also noted in a fourth document. After being briefed by Cohen on August 9, the commanding officer at Area One’s violent crime unit wrote a memo to CPD’s Internal Affairs Division asking them to investigate whether some officers might be working with Ashley. Strangely, even though the Area One detectives who’d been working the Ciralsky case had also been part of the task force that arrested Allen, Griffin, and Ashley that day, they didn’t file any reports to indicate a new lead on the case—not one, but two potential suspects. However, records show that Allen’s and Griffin’s fingerprints were run against those collected from the Ciralsky murder scene soon after their arrest: there were no matches.

The three documents that purported to capture Allen’s statements—Reardon’s GPR, Cohen’s memo, and the detectives’ Supplementary Report—were never introduced into evidence at trial. The detectives weren’t called to testify, either. Instead, the state put on their fellow prosecutor, Cohen, who testified about Allen’s statement using his own memo as a memory aid. The report produced by Reardon did make it into the hands of the public defenders representing Allen, but when they asked Cohen about it, he testified that he’d never seen it. His testimony was inconsistent with his own memo on several minor points, but the jury wouldn’t have known that since they never got to see it themselves. They wouldn’t have known that elements of the story that Cohen was attributing to Allen on the stand were more in line with the confession he and the Area One detectives had obtained from Henry Griffin.

Besides Darryl Moore, Henry Griffin was the only other person to implicate Allen in Gibson’s murder. Cohen questioned Griffin in the presence of a court reporter beginning at 11:58 PM, nearly ten hours after his arrest. He didn’t have a lawyer and in the transcript he agrees to waive all of his rights. Griffin’s statement, unlike Allen’s narrative and detail-rich account, is essentially a Q&A, with Cohen asking specific, even leading, questions and Griffin responding mostly with one-word answers. On several points, this version of the story differs from Allen’s.

Griffin confirmed that the hit on Gibson was ordered by Ashley and he did it in exchange for $2,500. He said that Allen was present when Ashley showed up at his apartment on June 20 and asked him to kill Gibson that night. Griffin said they went to Darryl Moore to get a gun. He also said that they were driving a blue rental car, while Allen had said they were in Griffin’s car but never specified its color or make.

Echoing Allen, Griffin said they left Moore’s and picked up three of his relatives and dropped them off at 93rd and Stony Island—where they picked up Gibson. He told Allen to drive, Gibson rode shotgun, and Griffin himself sat in the back. Cohen asked where Allen drove the car to, but Griffin doesn’t say anything about a stop to pick up quinine a few blocks away, instead he answered only: “Skyway.” He said they first got on it at 89th Street, drove south, then made a U-turn at the toll plaza and drove north.

Here’s the weird thing about this U-turn detail, which prosecutors would mention again and again during court proceedings: There is no entrance to the Skyway on 89th. And even if there was, driving south from there and then turning around at the toll plaza would have been impossible, since the toll plaza is at 88th—north of 89th. In Allen’s narrative (as captured by Reardon), there’s no mention of where they got onto the Skyway after picking up quinine, but he does say the pickup location was at 90th and Saginaw. The two streets don’t actually intersect, because of a park and the Skyway overpass cutting through the area, but there is a Skyway entrance ramp just two blocks from there, which would have allowed them to drive northbound, past the toll booths, and on toward the 73rd exit ramp. Even though Allen never mentions a U-turn in Reardon’s notes, Cohen wrote that he did in his memo.

Cohen and Griffin’s exchange about the murder is particularly laborious. Cohen asked what happened as they drove northbound on the Skyway.

Griffin: Carl Gibson was killed.

Cohen: Who killed him?

Griffin: I did.

Cohen: What did you use to kill him?

Griffin: A .38.

Cohen: How did you kill him?

Griffin: Shot him.

Cohen: How many times?

Griffin: Four.

Cohen: How close, in what part of his body did you shoot him?

Griffin: In the head.

Cohen: Where in the head?

Griffin: In the back of the head.

Cohen asked Griffin to demonstrate how close the gun was to the back of Gibson’s head by putting his finger to Cohen’s head. He then asks what happened to the body.

Griffin: It just sat there.

Cohen: Could you see pieces of his head go flying?

Griffin: No.

Cohen: Was there any blood?

Griffin: Yes.

Cohen: Where was the blood coming from?

Griffin: Back of the head.

Griffin didn’t mention his accomplice fleeing after the shooting. He said he pulled Gibson’s body out on the exit ramp and that he and Allen later dumped the rental car “out on 100-something [Street]” and gave the gun to Charles Ashley. Though Cohen wrote in his memo that the court-reported conversation happened after he’d talked to Allen, Cohen didn’t ask Griffin about Allen running away, making a tape about what happened, whether he threatened Allen after the murder, or about cops working with Ashley. He didn’t ask him anything about the quinine they were supposed to pick up for Ashley or the Robert “Doc” Ciralsky murder, either.

Before the interview ended, Cohen asked Griffin how he’d been treated while at Area One. “Nicely, nobody bothered me,” Griffin said. He confirmed that he’d been allowed to drink something and have cigarettes and use the bathroom. He confirmed that no one had beat him or forced him to say anything or made any promises in exchange for his statement, and also that he wasn’t under the influence of any controlled substances. At the end of the transcript, however, Cohen made a handwritten note that Griffin had refused to sign the confession and asked to speak to a lawyer.

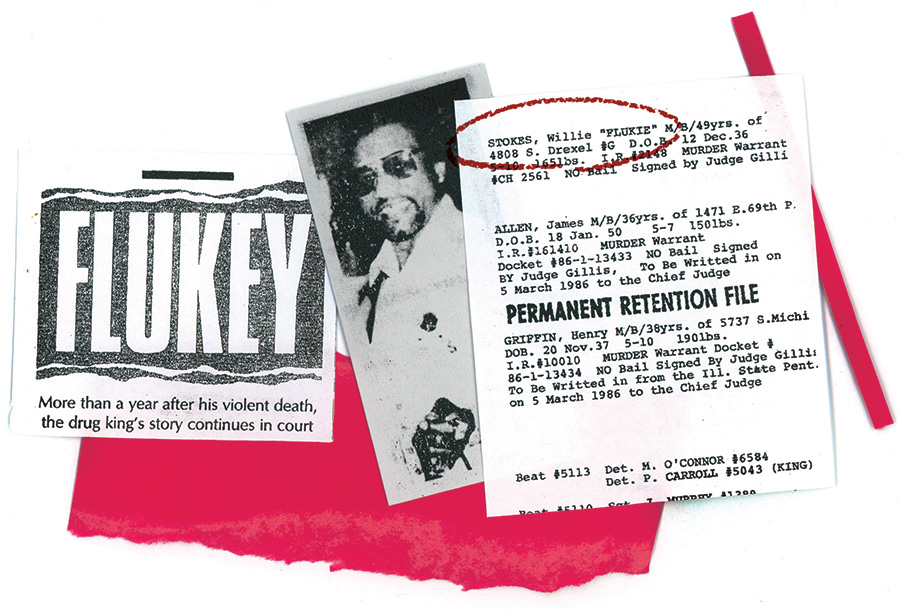

Griffin’s confession ultimately resulted in his conviction for Gibson’s murder. Judge Earl Strayhorn, who presided over the trials of all three codefendants, found Griffin’s actions so deplorable that he sentenced him to death. This was remarkable because Strayhorn, one of Cook County’s first Black judges, had been a staunch opponent of the death penalty, and had never sent anyone to death row in his 15 years on the bench. Speaking to reporters after the hearing, Strayhorn said he imposed the death sentence “strictly for punishment . . . I thought it was the only sentence that was warranted under the facts of the case. I never had facts like this before.″

In the late 1990s, Griffin, having lost all of his appeals in the state court system, turned to the federal court to get his conviction overturned. After several high-profile exonerations of innocent men who’d been convicted on the basis of coerced confessions, there was also a massive statewide push by advocates to get Governor George Ryan to commute the sentences of all defendants on Illinois’s death row. Northwestern University’s Center on Wrongful Convictions represented Griffin in his federal court case and in his clemency petition to the governor. Eighteen years after his arrest, a grim new story about what happened at Area One on August 9, 1984, came to light.

In the clemency petition attorneys laid out Griffin’s background as the victim of severe neglect, abuse, and molestation in his childhood, his history of mental illness, and his hardcore drug addiction. (His original defense lawyer failed to present these mitigating factors before his sentencing.) “Griffin was under the influence of heroin at the time of his arrest,” his attorneys wrote. In fact, on the barely audible wiretap tape with Moore, Griffin’s speech was slurred and disconnected and he became “increasingly incoherent to the point where twice during the recording he lapsed into unconsciousness.”

The lawyers argued that Griffin “was easy prey for the manipulations of the police during interrogations.” At first detectives told him that they were only interested in Ashley and Allen, and that if he confessed to the murder they’d work out a deal. Griffin said “the police wanted Allen as much as they wanted Ashley because Allen had previously killed a police officer.”

One of the women arrested with Griffin, Evon Knox, was his sister. When Griffin refused to make statements against Allen and Ashley, Pochordo threatened that Knox would be charged with the murder. While this was going on, Griffin could hear his sister screaming in another part of the Area One precinct. Like him, Knox had been “in and out of mental institutions” throughout her life, and Griffin feared that she “would not be able to psychologically handle being criminally charged.” Griffin also worried that if she was charged she’d lose custody of her children.

As he was faced with the choice of confessing and implicating two other people in the murder or seeing his sister charged, Griffin was going through heroin withdrawal and needed to use the restroom. The cops wouldn’t allow him to go, even after hours of interrogation, “until he eventually soiled himself,” his lawyers wrote. “Under the influence of drugs, humiliation, and threats to his family Griffin finally succumbed to the pressure and agreed to make a statement.”

According to Griffin’s clemency petition, the leading questions during the court-reported statement went hand in hand with “physical force” doled out by police officers “to make sure he answered correctly.” Whenever Griffin hesitated in his responses, the petition continued, “an officer standing behind him would dig his fingers into Griffin’s neck and shoulders, applying significant pressure that left bruises. When he did not know an answer to a question, the court reporter and other officers would leave the room, and leave him alone with the officer standing behind him, who would proceed to punch him about the body.” After each beating, Pochordo would come back into the interview room “and coach him as to the necessary facts.” After that, the court reporter and others would come back in and the on-the-record statement would resume.

Griffin confessed to the murder, his lawyers wrote, and implicated people who weren’t involved because he “knew that his statement could not be corroborated” and he thought that he would be “vindicated by the evidence.” But, rather than pointing away from him as the likely killer, his confession would only function as evidence of his guilt. Ultimately, Griffin was taken off death row when Governor Ryan commuted everyone’s sentences to life in prison. However, a federal judge declined to overturn his conviction.

Griffin made one last attempt to get a new sentence. During the hearings in 2011 and 2012, he was remorseful about having actually killed Gibson; multiple relatives, friends, and a psychologist testified that he had been admitting he was the shooter for years. Though he’d had a record of violence and violations during his earlier years in prison, the witnesses and prison reports showed that his behavior and outlook had changed. Cook County judge James Linn wasn’t convinced that he deserved another chance and imposed a life sentence again. “I’m not sure that it is in the interest of the rest of our society to have [Griffin] walking around as a free man,” Linn said. “He always seemed to find the wrong people to associate with. I am not sure I have confidence he’s ever going to make good decisions about that.” Griffin continued to appeal Linn’s decision in subsequent years, arguing that the judge should never have been assigned to the case due to his familiarity with the Gibson homicide—a few minutes before Linn announced his decision, Griffin learned that Linn (an assistant state’s attorney in 1984) was captured in one of the Gibson crime scene photos, standing next to the body. But his quest to get free was doomed. After contracting COVID-19 at Dixon Correctional Center last winter, Griffin died in prison on January 14, 2021. He was 73 years old.

Allen and Griffin never testified against one another. Nor was Griffin’s confession used against Allen at his trial. But neither was evidence that Griffin exculpated Allen as early as August 13, 1984. Just three days after their arrest, Griffin signed a statement saying, “On June 21st 1984 I alone, without the knowledge of James Allen shot and killed Carl Gibson.” At trial Allen’s defense attorneys wanted to enter the letter into evidence and argued that it wasn’t hearsay, and was as admissible as Darryl Moore’s testimony. Judge Strayhorn didn’t allow it. Less than three months before his death, in a message to Allen discussing the case, Griffin once again said, “You was set up!”

The Gibson case was classified as cleared and closed on August 12, 1984. The last investigative report, however, was filed by Reardon and Pochordo ten days later. An anonymous tip led the detectives to discover Griffin’s 1980 black International Harvester Scout (a two-door, Jeep-like vehicle) at a repair shop half a mile from the Skyway exit ramp where Gibson’s body had been found. The attendants at the shop told the detectives that the Scout had been there “for quite some time,” and identified a photo of Griffin as the owner. Evidence technicians noted “that the vehicle had been thoroughly washed.” No physical evidence of a murder was discovered in the Scout, nor any evidence linking Gibson or Allen to the vehicle. As for the blue rental car in which Griffin told Cohen he’d killed Gibson and then dumped on “100-something” Street—presumably covered in blood, and perhaps having a bullet lodged in its trim or a bullet hole shattering its glass—it was never recovered. No evidence related to this car would ever be presented at trial.

In the absence of any real evidence the cases against Allen, Griffin, and Ashley (who never gave any statements to police) relied on the stories told by Neil Cohen and the state’s other star witness—31-year-old Darryl Moore. Moore’s credibility, unlike the assistant state’s attorney’s, unraveled quickly when he took the stand on June 25, 1985.

Nearly everything Moore has ever said about himself in court, to the press, and on paper has been contradicted or denied, either by himself or others who know him. But one can get a sense of who he was and what he was up to the previous summer by triangulating between decades of statements and records. A member of the Disciples gang who’d done time for rape and robbery, Moore worked at a drug house on 47th and Indiana. He knew Griffin and Allen, but not very well. He’d known Ashley since he was a kid, because Ashley was lifelong friends with Moore’s father. Moore claimed on the witness stand that he took contracts to beat and kill people from “whomever, you know, wish to hire me to break somebody’s legs or to murder someone. It is for profit.”

Moore’s testimony—often spoken or mumbled so incoherently that he was repeatedly asked to keep his voice up—was riddled with inconsistencies. He was impeached on the stand multiple times throughout the trial. (On one day of testimony, he both admitted to and denied being involved in the 1980 murder of a sex worker.) He denied telling Pochordo many of the details the detective had attributed to him in his warrant affidavit, including that he’d supplied him with information about other homicides. Information about the dates he allegedly met the defendants, what they talked about, who had which weapons, the money offered by Ashley to kill Gibson, and other details were scrambled.

Ashley’s defense attorney, Sam Adam, eventually brought in Moore’s mother and brothers to testify that they wouldn’t believe him under oath. Two of Moore’s brothers testified that he had bragged for several years that “even if he went to jail, he could always get out of jail by telling the big, fat honkie Pochordo any story.” Adam also tried to establish that Moore wanted revenge because he believed Ashley was responsible for the murder of his 14-year-old brother.

Allen’s public defenders also painted Moore as having a vendetta against Allen. One witness testified that Moore had told him that Allen “had embarrassed him or did him some type of wrong,” and that Moore vowed to get even. (There was at least one other potential witness who could have testified that Moore was setting Allen up to take the fall for the Gibson murder, but he was never called.)

In exchange for his trial testimony in this case, the state had dismissed Moore’s pending drug and gun charges and allowed him to plead guilty and get time served for an armed robbery. It would later come to light that the state paid him more than $65,000 in cash, rent, car bills, hotel stays, plane tickets, and even bought him a food truck. He said he lived a “lavish lifestyle” and continued to sell drugs while getting payments and protection from the police department and State’s Attorney’s Office.

Moore began recanting his testimony in the Gibson murder case a year after the trial. In a videotaped conversation with Ashley’s and Griffin’s attorneys, he said he never met with Ashley to discuss a contract hit on Gibson. He said he lied about meetings with Griffin to plan the murder, and about Griffin and Allen admitting to him that they killed Gibson. “I told the lie under oath,” Moore said on the recording. “Mike Pochordo told me basically everything to say.” Moore said the information in the sworn affidavit Pochordo submitted to get a warrant to arrest Ashley, Griffin, and Allen, which cited him as a reliable source, was “totally false.” When the lawyers asked if he knew why Pochordo wanted him to lie, Moore said that the detective “suspected Chuck Ashley of being behind about eight killings and he wanted a big bust.”

Moore also claimed that the prosecutors built their case on lies. He said that at one meeting with Pochordo and several assistant state’s attorneys, Cohen said “he would give anything up in the world to sustain a conviction against Chuck Ashley.” Years later Moore stood by the video recantation during federal court testimony.

Of course, since Moore’s own family members testified that they wouldn’t believe him under oath, there’s reason to doubt anything he said. As a result of this case, his unreliability as a witness—and the state’s willingness to pay him to get convictions—became notorious in Chicago legal circles. “Nothing good can be said of Darryl Moore. He is a hit man, drug pusher, robber, rapist, junkie, parole violator, and perjurer,” a 1987 profile of Moore in Chicago Lawyer magazine began. Moore was also profiled as a “quintessential snitch” in a 2004 Center on Wrongful Convictions report on jailhouse informants’ testimonies being the “leading cause of wrongful convictions” in U.S. death penalty cases. Indeed, according to the report, “the first documented wrongful conviction in the United States involved a snitch” who, in exchange for his own charges being dropped, was placed in a cell with a murder suspect in 1817 Vermont. The snitch testified that his cellmate confessed to killing a man—the man was later found alive. The Center found that recanted and discredited snitch testimony accounted for nearly half of all death row exonerations since the 1970s. “When the criminal justice system offers witnesses incentives to lie, they will.”

In 2002 Moore, Pochordo, and Cohen were called to testify in Griffin’s federal case, during the course of which it was confirmed that the state spent tens of thousands on Moore to be a witness. Moore (who was then incarcerated for the 1987 rape of an 11-year-old girl, which occurred while he was living large on the state’s dime) continued to assert that he lied about everything and that the state knew that. Pochordo, meanwhile, stood by everything he’d written in his reports and warrant affidavit but repeatedly said he didn’t recall any details about the case. He claimed that he didn’t know Moore was being paid thousands by the State’s Attorney’s Office. Cohen also denied knowing anything about the specific payment arrangements his office had with Moore, and said he wasn’t the one responsible for his charges being dropped. He did admit that he knew Moore to be a liar. “Darryl would probably say anything to get more money out of the State’s Attorney’s Office,” Cohen testified.

Remarkably, Moore wasn’t the only jailhouse snitch deployed against Allen. Perhaps fearing that Moore wouldn’t be a solid enough witness on his own, the state also called 62-year-old Sherman Overstreet, who had been part of Ashley’s drug operation and became a police informant. He testified that just two weeks before the trial, while housed in protective custody at the Cook County Jail, Allen talked to him one-on-one about his involvement in the Gibson murder. Allen himself was briefly in the witness quarters because the state offered him a deal to plead guilty and take a six-year sentence, which he says he ultimately turned down because he didn’t want to go along with what he characterized as the “lies” from Cohen’s memo. And he was sure he’d beat the case. Overstreet said Allen told him that he had been the driver, and that “he wore tight gloves, driving gloves, to keep from leaving fingerprints.” He said Allen described driving on the Skyway with Gibson and making a U-turn at the toll booth. When Allen’s attorneys cross-examined Overstreet, he admitted that he had pending charges for selling drugs and that he’d made a deal with prosecutors to get time served in exchange for his testimony.

If Allen was on trial today, it’s likely that neither Moore nor Overstreet’s testimonies would be admissible against him. Since 2018, Illinois law has required pretrial reliability hearings for informants testifying in murder and other high-level felony cases. Prosecutors have to disclose any plans to use trial testimony from jailhouse informants at least 30 days in advance. They also have to disclose what they offered informants for the testimony and any other cases in which the informants were used.

Despite the shakiness of the jailhouse snitches’ testimonies and the total absence of physical evidence tying him to the killing, the jury found James Allen guilty of the murder of Carl Gibson on July 2, 1985. As was typical in the pre-DNA era, it was a case built entirely on stories. These stories, like all stories, hinged largely on the perceived credibility of the storytellers.

Allen didn’t testify at his own trial (neither did Griffin or Ashley). This was likely because his lawyers wanted to prevent the state from grilling him about his prior criminal record and murder conviction. Besides asking the judge to declare a mistrial at least five times during the proceedings, his attorney also filed a motion for a new trial after the verdict and was denied.