Abierre Minor has been a commuter since she was five years old, taking the 79 bus daily to her elementary school. Public transit has always been the main way she gets around the city but, over the past few years, she’s felt she can’t rely on it to get places on time.

“Connectivity issues have always been a thing. But ghost buses have definitely stopped us and hindered our ability to navigate the city. I’ve had several experiences where I’ve essentially been waiting at a bus stop, looking at my transit app, expecting the bus to come, but then it never came.”

She remembers one time when she was headed from the Loop to a phone-banking event on the south side. She waited for the 6 bus for over an hour, but the Ventra app kept saying the bus was three minutes away. Eventually, she gave up and took a rideshare service home.

That’s what brought her to organize town halls with the People’s Lobby on how poor transit access impacts Chicago’s communities of color. “The cost is great, depending on why you’re on the bus and the environment at your stop. Because you’re essentially stuck in that space until you can get on the train. You’re taking people’s ability to navigate the city of Chicago and people’s ability to show up for work or to be reliable or plan to be in whatever spaces they’re called to be in.”

For some longtime riders, ghost buses and late-arriving trains drove them away from train platforms. Service cuts in recent years, largely due to ongoing staffing challenges, have also made it harder for passengers to rely on transit to get to places on time.

“There’s a potential negative feedback loop of ghost buses or long gaps between buses and trains. People get discouraged and don’t want to ride, and that’s less fair revenue for the system,” says Kate Lowe, a professor at the University of Illinois Chicago. “There’s a lot of human cost to unreliable service that is distributed unequally.”

In recent years, Chicago has seen big shifts in how people travel. Ridership plunged during the pandemic. It’s been slow to recover. By 2023, about two-thirds of riders had returned to the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA). But the rise of remote work cut down on trips to the office. Meanwhile, biking has doubled in the past five years, and rideshare services like Uber and Lyft have stayed popular since their inception, possibly drawing some passengers away from public transit.

A written statement from CTA says, “We have seen ridership grow in recent months as service has been added as a result of our aggressive hiring efforts. 2023 was a year marked by breaking post-pandemic ridership records and building off that growth, 2024 has been no different . . . We do believe we will get our ridership back over time, but it’s not going to happen overnight.”

There’s no single factor that explains why these missing riders have so far continued to shirk public transportation. But a Reader analysis of transit data and interviews with organizers and experts unpacks how recovery has squared across the city.

In May of this year, the CTA saw an average of one million weekday riders for the first time since the start of the pandemic. But ridership has yet to rebound to 2019 levels. The CTA recorded an average of about 913,000 weekday riders this March, compared with more than 1.4 million during the same month in 2019.

For comparison’s sake, each year captures ridership data from March to the following February. This is so the ridership data in 2020 isn’t biased by including the first two months of pre-pandemic ridership and so we can include the full year, since ridership changes are often seasonal.

The Pink, Orange, and westbound Green Line trains made the most progress in closing the gap between pre-pandemic and post-pandemic ridership. Compared with 2020, they all saw recoveries of 60 percent or more in 2023. Meanwhile, the Blue Line train west to Forest Park lags at just 42 percent of its pre-pandemic ridership. The Yellow Line and Red Line south to 95th also saw weaker recoveries.

“I think a lot of Oak Park and Forest Park folks are shifting [transportation] modes,” says Lowe of the westbound Blue Line’s lagging ridership. “But one other factor is the majority of that corridor is a rail slow zone, so that’s pretty discouraging. Sometimes, there are some really long waits, so people are opting out.”

Slow zones are areas where trains operate at slower speeds (15–35 miles per hour) because of deteriorating track quality or to allow construction on the tracks. As of May, the Blue Line has more slow zones than any other CTA rail line—encompassing almost three-quarters of the ride to Forest Park. While there have been slow zones there since 2012, the share of slow zones on the Forest Park line has nearly doubled from 2019 to today.

| CTA Rail Line | Post-Pandemic Recovery |

| Blue Line to O’Hare | 59% |

| Blue Line to Forest Park | 42% |

| Red Line to Howard | 56% |

| Red Line to 95th | 53% |

| Green Line to Harlem | 63% |

| Green Line to 63rd | 60% |

| Orange Line | 65% |

| Pink Line | 74% |

| Brown Line | 58% |

| Purple Line | 59% |

| Yellow Line | 52% |

| Loop | 52% |

Much of the line’s tracks were built in the 1950s and have long needed significant upgrades. But slower and, thus, fewer trains mean longer wait times for passengers, which might be pushing them toward other options. Many neighborhoods along the Blue Line are also near the Green or Pink Lines, suggesting people could’ve also moved their commutes to another route.

The southbound Red Line’s struggle to attract riders back is more complicated. Even before the pandemic, Black residents in the south-side neighborhoods it served faced longer commutes to work—but also longer trips for groceries and health-care visits—than their white neighbors on the north side. Transit unreliability may have compounded the problem, making it difficult for residents in economically disconnected areas to get to work on time.

“Black residents are more likely to use transit to make these trips,” says Craig Heither, principal analyst at the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP). “But by transit, by walking, by driving: in every case, it took Black residents longer to get where they needed to go.”

Alder Will Hall, 6th, has seen longtime riders on the far south side become frustrated with unreliable service. “The ghost buses [and] trains . . . they have really made life inconvenient. There have been instances in which people have to prove ten times over that they were not late for work because they were unprofessional but mainly because of CTA. I think that we need to continue to listen to people that ride the trains—including myself—and I think we can see basic improvements.”

Sativa Volbrecht lives in Bronzeville. She never considered buying a car; she’s concerned about its impact on the environment. That’s one of the things that pushed her to colead Sierra Club Chicago’s transportation team. Since the start of the pandemic, she says, “I’ve had to increase my buffer time for commuting and getting anywhere because there might be unexpected delays. If I miss the bus by 30 seconds, the next one’s not coming for 20 minutes now. So I add so much more buffer time than I used to because there’s such a high chance that one thing goes wrong and it offsets my entire journey.”

Usually, she sticks it out and waits on the Green Line train platform. But recently, she’s resorted to canceling plans with friends or trips outside her neighborhood. Once, on her way to a fitness class on the north side, she got so frustrated with the amount of time she spent waiting for the train that she decided to eat the cost of the class and went home. “It’s really difficult to gauge how busy the trains will be,” she says, “and part of that is because of delays.”

For many who’ve swapped their Ventra cards for something else, their travel changes started before the pandemic.

The best way to win back riders, according to Lowe, is more frequent and reliable service. That’s something the CTA has struggled with, especially as it deals with staffing shortages that have impacted transit systems across the country. “Some transit systems, such as New York and Washington, D.C.’s, have recovered. But right now, the CTA is still understaffed. We don’t have enough operators in the CTA system to run service levels that match our pre-pandemic service.”

“More frequency encourages more people to ride; more people riding helps you feel safe,” Lowe continues. “A lot is beyond the CTA’s control. But providing frequent, reliable, quality service can have a positive feedback loop.”

In 2023, total annual ridership surpassed 60 percent of 2019 ridership. Interviews with experts and transit riders indicate riders’ slow return to transit could be a result of a little bit of everything.

For many who’ve swapped their Ventra cards for something else, their travel changes started before the pandemic. Remote or hybrid work was already on the rise in 2019. A CMAP survey of workers that year saw 14 percent of residents in northwestern Illinois telecommuting at least once a week—a jump over the past decade.” We’re still seeing higher rates of people working from home than we did before COVID,” Heither says, but “a lot of that is not people working from home all the time. It’s people doing more of a hybrid schedule where they’re going to their place of work at least some days of the week.”

Working from home also doesn’t necessarily mean fewer trips on public transit, says W. Robert Schultz III, campaign organizer with the Active Transportation Alliance. “A lot of the literature and talk around using public transportation is about commuting to jobs. But a great deal of where people use public transportation is to go shopping and meet their medical needs, education, and recreational activities.”

Most Chicago residents who work from home live downtown or on the north and northwest sides, according to 2021 census data. Yet rail ridership has had lower rates of return on the Red and Green Lines going south and the Blue Line going west, where remote work is less common.

Working from home might only be one part of the picture. “Sixty percent of the jobs in the Chicago region still have to be performed in person. They can’t be performed remotely,” says Kendra J. Freeman, vice president of programs and strategic impact at the Metropolitan Planning Council. “There were service cuts dating back to before COVID, and they’ve only gotten, in some cases, worse.”

Rideshare services may also be drawing folks away from public transit. “Sometimes, if they have the economic wherewithal, they’re substituting those trips with Uber or Lyft . . . [or they] are using their own personal bikes,” Schultz says.

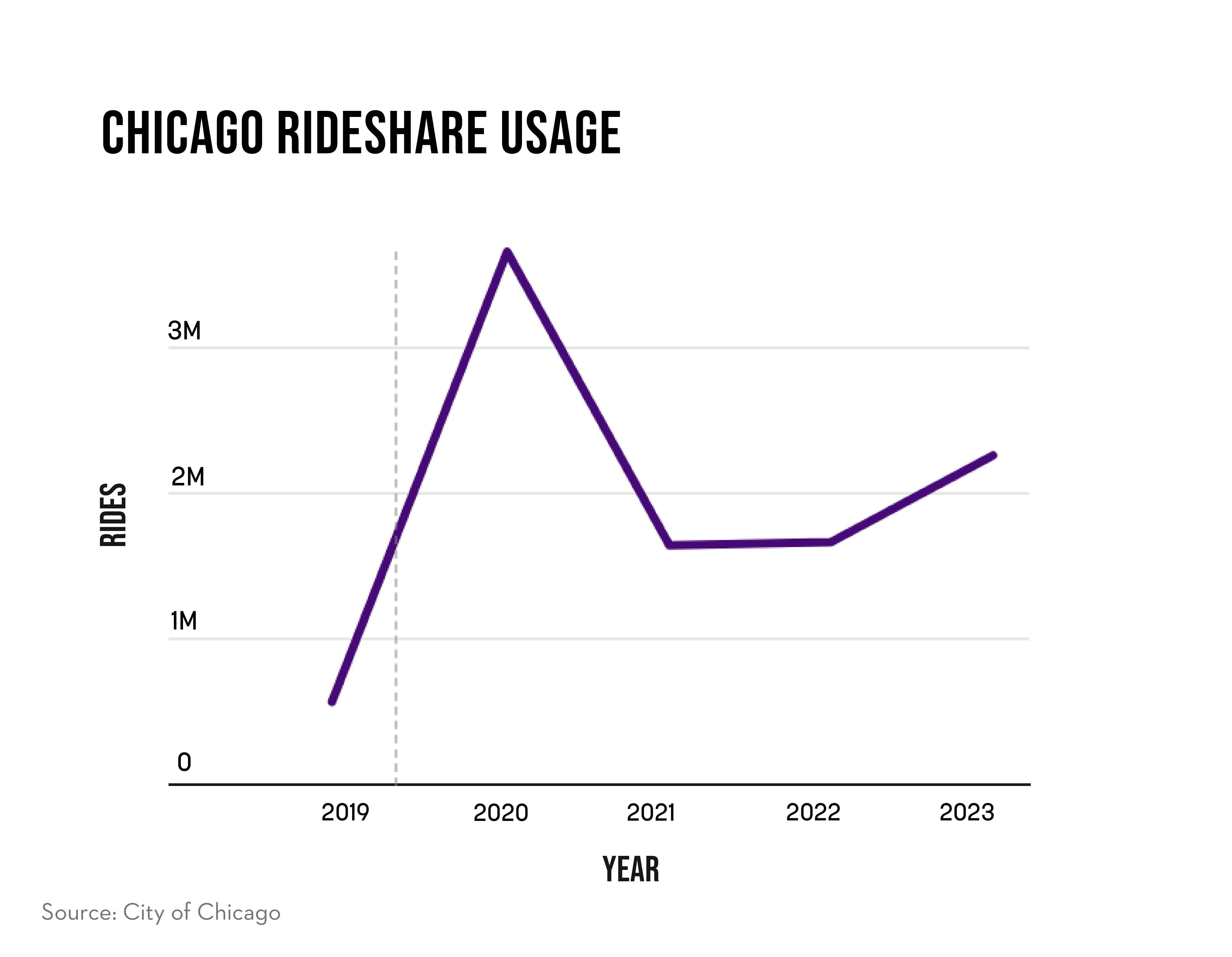

Chicago’s rideshare apps took a big hit from COVID-19. Trips in 2020 dropped by 55 percent compared to the year before. But they’ve rebounded a bit faster than public transit. In 2023, rideshare apps logged nearly three-quarters of the trips they lost.

“What we don’t want to see is a continual uptick in people getting in cars, especially when they’re taking single-vehicle rides,” says Freeman, “because that not only has traffic implications but also environmental implications. People are concerned about being able to have transit be there to get them where they need to go, on time.”

Jack Hamilton moved to Chicago in 2021. He wanted a car-free lifestyle, one he couldn’t have in Atlanta where his options were limited. But on the days he has to go into the office, he dreads his commute. During the morning rush hour, sometimes train cars pass by without any room to take on new passengers.

“It is just packed in there like sardines. . . . I’ve sat there on the bench and seen people miss four trains because they are completely packed full. Nobody on there is having a comfortable ride.”

He doesn’t like the idea of getting in a car, but he’s using rideshare apps more often. Just as often, though, he’ll just forgo the trip entirely. Lately, he says it’s started to feel like the CTA is pushing him away. “It frustrates me that I can’t make a good argument for why we should take the train when somebody’s like, ‘Let’s just do Uber,'” he says. “Because at the end of the day, it’s going to take longer, [and] it’s going to be kind of uncomfortable.”

For some, biking has replaced trips they would have normally taken on public transit.

Floylice Lawnicki first started biking seriously during the pandemic. Breezing through bike lanes was her way of spending more time outdoors and avoiding COVID-19 on the train. But when the lockdown ended and people began returning to the CTA, she stayed on her bike.

“I live a totally different lifestyle now. I still like public transportation, but my bike is going with me. My bike goes on the front of the bus, on the train,” she says. “Everything is planned around my bike.”

She loves zipping past cars stuck in traffic on DuSable Lake Shore Drive and navigating the city on her own. Her bike has become her prized possession, her main mobility option. “Public transit became less reliable, and I just don’t like depending on anybody. I depend on my bike. We have no boundaries; I can go anywhere.”

Chicago’s bicyclists have more than doubled in number in the past four years, according to a study by the Chicago Department of Transportation and mobility data company Replica. They saw a surge in people without cars resorting to bikes for transportation in every neighborhood.

Haley Wilson remembers the day she stopped taking the CTA quite vividly. She stopped riding regularly during 2020’s protests against police violence, a day after former mayor Lori Lightfoot infamously raised the bridges to the Loop and suspended transit services downtown. She was on the 80 bus headed to work when the bus driver stopped at Western and told everyone to get off. “I, literally that day, was like, ‘I’m just going to dump my savings account and buy a bike.’ Because by that point . . . service had already started being cut.”

“Now, I bike everywhere,” she continues. “I get a lot of my time back, which gives me more freedom.”

It’s also possible that some south-side commuters substituted their CTA trips with Metra, especially as pilot programs beginning in 2021 halved ridership fares for passengers. Like the CTA, Metra also saw significant ridership declines since the pandemic. Its strongest recovering line is Metra Electric, where its stations on the south side hit an average of 90 percent of pre-pandemic ridership in 2023, according to data received via a Freedom of Information Act request.

Every day, Chicago sees hundreds of thousands of people move through the city. It shapes access to employment, space, and education. From an equity standpoint, public transit matters because, when you don’t live near “opportunity,” getting there as fast as possible matters.

“Ridership growth is affected by many factors outside of CTA’s control. However, we expect that more people will continue to choose public transit because it is still the most cost-effective, time-saving way to get across Chicagoland and it’s better for the environment,” says CTA in a written statement.

“There’s a lot at stake for Chicago collectively,” says Kate Lowe. “Because if people opt out of transit and are on the roads driving, that’s terrible for the environment [and] . . . terrible for safety. . . . Poor-quality transit is devastating from an equity perspective.”

“Public transit became less reliable, and I just don’t like depending on anybody. I depend on my bike. We have no boundaries; I can go anywhere.”

Chicago’s public transit agencies are nearing a fiscal cliff. When ridership shot down during the pandemic, $3.5 billion in federal COVID-19 relief funding kept the CTA afloat. The state legislature continued to dole out federal aid for the past couple of years. But now, the Regional Transportation Authority (RTA)��responsible for CTA, Metra, and Pace—faces a $730 million shortfall when it expires in 2026.

“Transit agencies have been living on that because ridership has been down, not only here but across the country. So those funds are going to run out in 2026, and a lot of people have not come back to transit,” says Jacky Grimshaw, senior director of transportation and policy at the Center for Neighborhood Technology. “We need to have a new way of funding transit. We can’t just rely on fares.”

Part of the problem is how Illinois funds public transit. By relying so heavily on fare revenue to support the agencies’ budgets, the transit systems under the RTA are more vulnerable to ridership changes.

Illinois law requires Chicago’s transit agencies to earn half of their revenue through ridership fares—one of the highest “fare box recovery ratios” in the country. The statute has been on the books since 1974, when state lawmakers hoped to impose “fiscal discipline” on transit boards. It’s made the CTA sensitive to ridership changes over the decades—and, since the pandemic drove riders away, compliance has been impossible without drastically cutting service.

RTA and CMAP, along with transit advocacy groups, have been lobbying the state legislature to reassess and reduce the farebox recovery ratio throughout the pandemic. New legislation on the horizon seeks to merge CTA, RTA, Pace, and Metra into the Metropolitan Mobility Authority and completely change how current CTA is funded, securing an extra $1.5 billion in funding each year.

But many advocates think it’s a moment to rethink how public transportation is defined—whether that means luring drivers off the road, competing with other options for getting around the city, or reestablishing trust with people who’ve opted out of the system.

“We’re hoping that [by] providing better and more frequent service, people will start to recognize the advantage of using transit, rather than using automobiles,” Grimshaw says. “People use cars because they can’t count on transit. But if we had enough frequent transit [and] operators, they wouldn’t have to worry about getting home or being late to work.”

There’s a lot up in the air for ridership recovery at the moment. If the CTA’s ridership falls because of permanent shifts to the status quo—like remote work—it may still struggle to rebound to 2019 levels. But if people are leaving public transit behind because they feel like they can’t count on its reliability, what wins them back is more frequent, reliable service.

Some commuters feel that the CTA hasn’t been held accountable for lagging service or performance issues. Twenty-nine alders signed on to a resolution in May calling for CTA president Dorval Carter to be fired—but he’s still at the helm.

Organizers feel the time is ripe for change. “Our public transportation needs to be safe; it should be reliable, affordable, and efficient,” says Abierre Minor. “I believe that some of the connectivity issues we see on the south and west sides are intentional, and the cost is great. I believe the residents of Chicago are demanding more. And they have a right.”

For more in-depth Reader reporting on the CTA, from the archives…

🚏The moment met the CTA

🚉 City Council talks transit accountability

🚌 CTA employees share the personal cost of working inside the nation’s second-largest transit agency

Editor’s note (7/15/24, 9:45 AM): This story was updated to clarify that Kendra J. Freeman works for the Metropolitan Planning Council, not the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning.