Walking toward the Canalport Riverwalk, a crane lifts shredded metals as traffic speeds toward a bridge. A flashing sign alerting drivers of pedestrians doesn’t work. Visitors aren’t expected on this stretch of the Chicago River’s south branch. But they’re here. Fishermen, couples on dates, kayakers, rowing teams, even the occasional Jet Ski rider. They all make appearances at the narrow plot of land that juts into the water just west of Ashland and just north of 31st Street in Bridgeport.

One gloomy weekend in early June, there’s even a festival.

The University of Illinois Chicago’s Freshwater Lab is hosting the fourth iteration of its Backward River Festival along the Riverwalk. The goal is to educate the public about rewilding the river, the importance of keeping the water clean, and—the literal shadows hanging over this year’s event—saving the Damen Silos, the city’s first skyscrapers.

Over the course of decades, the river has come a long way from the dumping ground it once was. Sage Rossman, community outreach and programs manager from Urban Rivers, an organization that transforms urban waterways into wildlife sanctuaries by incorporating gardens and walkways, says it’s been “no small feat.”

Where the Riverwalk is located today, there was once an area of riverside shanties filled with immigrant laborers promised opportunity in the 1800s. As industrialization in Chicago boomed, steel mills and lumber yards dumped waste into the river. In 1865, the infamous Union Stock Yards opened nearby. At Bubbly Creek, just south of the Riverwalk, methane gases from discarded cow and pig carcasses rose from the bottom, forming rancid bubbles. A thick, hard grease formed that chickens and people could walk on.

While the south branch got a bad reputation, the whole of the river was in despair. The city’s sewage system mixed with the animal waste and emptied into Lake Michigan, our primary source of drinking water. Cholera, dysentery, and typhoid swept the city, especially the lower-income communities living and working near the river. To prevent an epidemic, the city needed a solution.

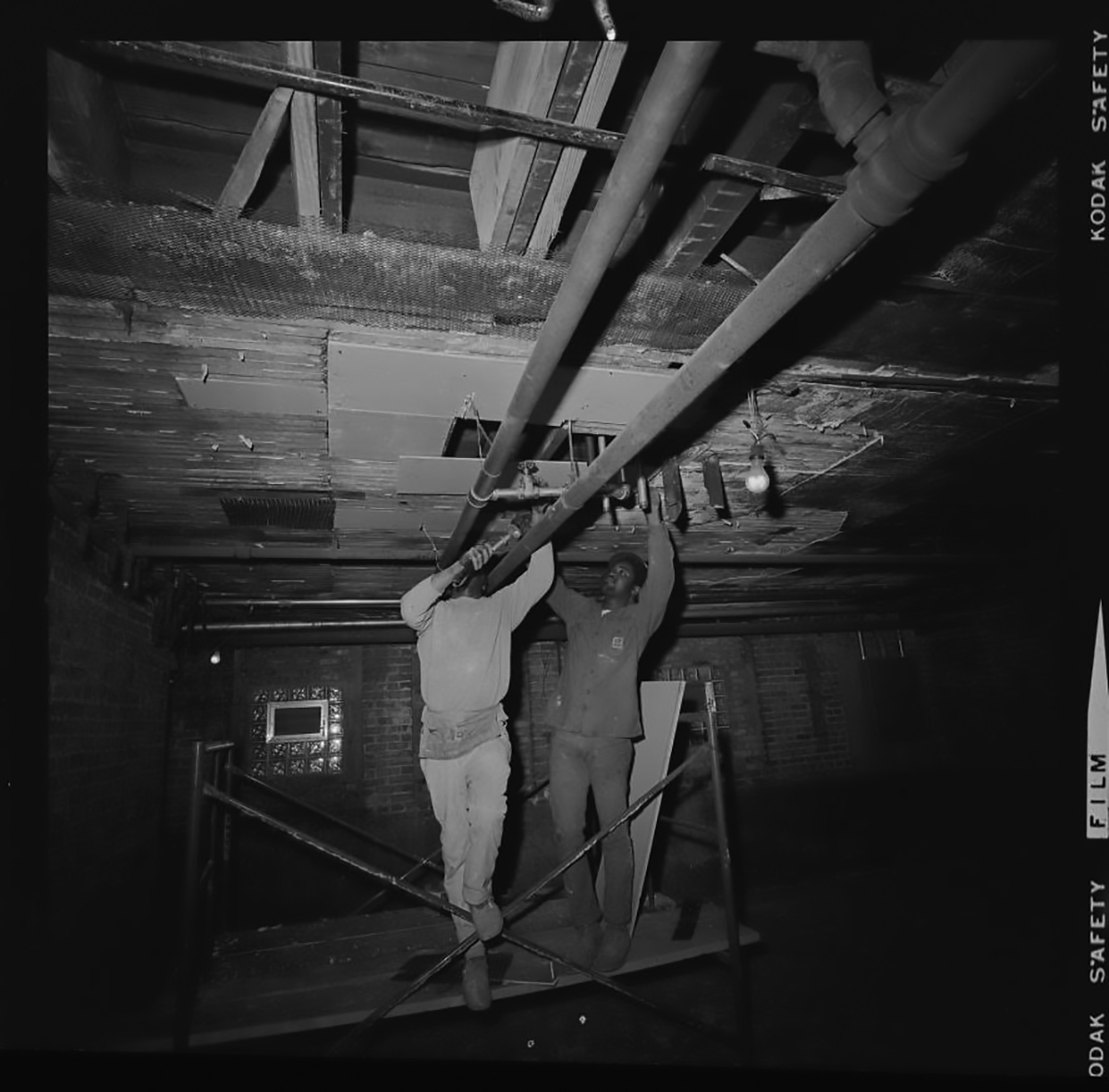

In 1892, officials hired construction crews to create canal locks. They also dredged, deepened, and widened the river—which emptied into an entirely new canal called the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal—to reverse its flow. Since then, the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District (MWRD) can be credited with most of the river’s cleanup. Even after the river’s reversal, Chicagoans continued to dump waste into the river, so the MWRD installed additional sewer pipes to divert wastewater away from the river. Since the 1990s, the district has been working on the Tunnel and Reservoir Plan (TARP), a deep tunnel system that forces rainwater to water reclamation plants, where it’s cleaned before being released.

Today, the river isn’t perfect. The bottom of Bubbly Creek still contains metal contaminants and industrial chemicals. Nevertheless, it’s resilient. In 2022, scientists at Shedd Aquarium found the south branch had more diverse fish species than anywhere else in the Chicago River.

That same year, Urban Rivers and Shedd installed floating gardens to restore habitat for native wildlife in challenging areas. Rossman explains, “These gardens are full of native wetland plants that grow hydroponically through the garden modules into the water, providing quality habitat both above and below the water’s surface. They mimic a normal midwestern wetland habitat, creating a natural foothold within highly urbanized waterways.”

At the festival, these accomplishments are on display. Local vendors pass out informational packets, host bird-watching workshops, teach festivalgoers about soil health, create seed bombs, and promote open discussions about why our waterways matter.

With a stage set up against the backdrop of the river and the Damen Silos, performances include a water ritual by drag artist Loteria, a performance selection by the Free Street Theater, music by Jarochicanos, and an opera by Chicago Fringe Opera. Speeches from local activists and advocates, such as the Pilsen Environmental Rights and Reform Organization and the Warehouse Workers for Justice, are interspersed between performances.

Rossman says she’s “consistently amazed at the enthusiasm with which Chicago’s communities, especially on the south branch, engage with the river when it is made accessible and approachable to them.” Urban Rivers and the South Branch Park Advisory Council offer free community kayaking out of Park Number 571’s boathouses. June kayaking dates sold out in two and a half days. “The river hosts multidisciplinary problems,” Rossman says, “which must be met with multidisciplinary solutions. And I think this festival is a fantastic example of those networks aligning for impact.”

In addition to Chicago’s waterways, the festival focuses on the fate of the Damen Silos on the opposite side of the Riverwalk. We can’t access them, but it’s the closest the public can get to these monuments to Chicago’s past. In 2022, Michael Tadin Jr. purchased the grain silos from the state for $6.52 million—double the initial bid. Tadin is the owner of MAT Asphalt, which in 2023 agreed to a $1.2 million class-action lawsuit settlement after McKinley Park neighbors said the plant was polluting their neighborhood. MAT Asphalt said the plant’s emissions were below regulatory limits and denied wrongdoing.

The silos were built in 1906 and are one of the last standing remnants of the grain and agricultural industry that built Chicago. They stored wheat, corn, and barley that would eventually be sold at the markets. They’re why Carl Sandburg called Chicago the “Stacker of Wheat.”

In 1977, layers of grain dust packed in the silos mixed with the heat, causing an explosion and leaving them closed for good. They soon became popular destinations for ruin porn enthusiasts and were the backdrop for a 2014 Transformers movie. But now, the silos’ future hangs in limbo. Tadin is working with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Historic Preservation Division of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, and the Chicago Department of Public Health to obtain five demolition permits and address environmental concerns. Tadin tells the Reader it’s a “federally regulated process,” and he says various steps need to be taken for the “site’s historic elements to be preserved.”

Rachel Havrelock, director of the Freshwater Lab, says if the silos aren’t saved, “then the 2024 Backward River Festival will be a kind of silos’ last stand, a celebration of a significant waterfront site, and a coming together of people who hope to shape the future of the south branch of the Chicago River in positive ways.” She’s hopeful, however, that they can be “repurposed in ways that benefit the community.”

Area residents have asked the federal government to preserve the silos. In 2022, Neighbors for Environmental Justice asked the state to suspend their plan to sell to Tadin. A month later, they and several other southwest-side community groups and elected officials released a letter to Governor J.B. Pritzker demanding he stop the sale. The Army Corps told residents at an early 2024 community meeting in McKinley Park that the demolition would have an “adverse historical effect.” Tadin says that despite all the pushback, they’ve “given great consideration to what community members have shared about the property’s future.”

Other cities have studied and celebrated grain elevators as architectural artifacts. Silo City in Buffalo, New York, is now a waterfront venue. And the Canada Malting Silos in Toronto are currently undergoing development to become a public park, art center, and event plaza.

Colin Smalley, the Army Corps’s Damen Silos project manager, says the Chicago Park District is continuing its work to find a solution to memorialize the silos. While he says that they don’t have a final idea, they’re close to drafting an agreement. Smalley says the parties involved discussed numerous ideas, like repurposing the silos as a walking path or displaying a collection of historical photos. Regardless of ultimate plans for the silos, any new development along the river requires a 30-foot setback from the water for public access.

In addition to the silos’ historical significance, residents are also concerned that their demolition could impact air and water quality. Havrelock worries dust, debris, and pollutants could blanket the neighborhood if the massive structures are torn down, like what happened in Little Village in 2020, when a discontinued industrial smokestack imploded and cast a massive cloud of toxic dust over the southwest side.

Asked about possible impacts on the waterways and community, Tadin says he’ll continue to abide by regulations related to the property and demolition. And he says safety is a concern at the silos in their current state. “Although we have retained multiple security staff for the property, trespassing and other criminal activity continues to occur. I am very concerned that it’s not a matter of if, but when, something tragic happens there. It is vital that this process keeps moving forward for the sake of people’s safety.” He says there aren’t any concrete plans for the Damen Silos and remains “committed to seeing the historic review process through to completion.”

Havrelock hopes she doesn’t see the silos come down. But she says, “If we do, then our intent for the festival is to have eyes on the site and on the demolition in the name of protecting residents, air, water, birds, fish, and the safety of Chicago’s southwest side.”